Rapamycin Dosing for Longevity: What Emerging Human Research Reveals About How Dose and Timing Shape Autophagy Without Compromising Metabolic Health

Rapamycin targets a conserved growth pathway repeatedly linked to aging. In multiple species, chronic mTORC1 overactivation drives age-related decline; rapamycin extends median and maximal lifespan in mice by ~15–36% depending on sex, strain, and timing of intervention.

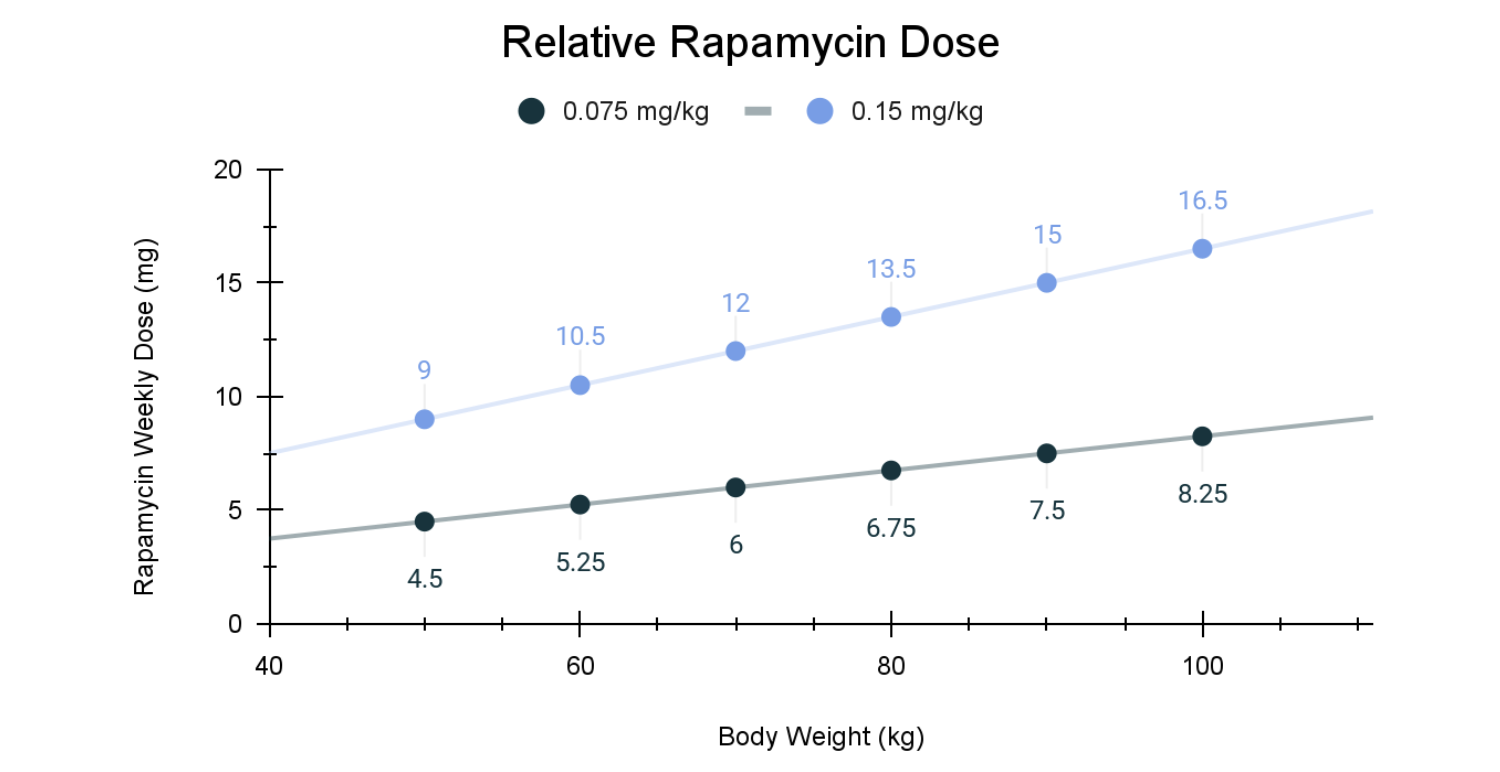

Low-dose rapamycin for aging is typically discussed in the range of ~0.075–0.15 mg/kg once weekly, which corresponds roughly to 5–10 mg/week for a 70 kg adult, far below doses used in transplant medicine.

Much of what we know about dose–response for longevity comes from mice and dogs, especially the Dog Aging Project, where 0.15 mg/kg once weekly was chosen to balance meaningful mTOR inhibition with low risk of immunosuppression.

Early human studies show immune enhancement, not suppression, at low doses. In older adults, everolimus (0.5 mg/day or 5 mg weekly for 6 weeks) increased influenza vaccine response titers by ~20% and reduced PD-1–positive exhausted T cells, without increasing infection risk.

Body size, age, comorbidities, and drug interactions likely influence the “right” dose: mg/kg scaling, reduced kidney function, polypharmacy, and baseline immune status all change rapamycin exposure and risk.

Effective human dosing appears broader than initially assumed. Real-world and trial data suggest that weekly doses in the ~3–10 mg range can engage aging-related pathways, with circulating levels below those associated with transplant-level immunosuppression (>20 ng/mL).

Human longevity trials are still early—but signals are accumulating. While no trial has yet demonstrated lifespan extension in humans, early studies report improvements in immune function, cardiometabolic markers, muscle-related biomarkers, and patient-reported outcomes, supporting continued investigation of low-dose intermittent rapamycin.

Until larger, longer trials are complete, low-dose rapamycin for longevity remains experimental and should be framed as a research question not a finished clinical playbook.

Introduction: A background on the mTOR-driven cellular growth imbalance that propels aging

Rapamycin is the most consistently effective pharmacological intervention for extending lifespan across a wide range of model organisms, including yeast, worms, flies, and multiple mouse strains [1]. Over the past two decades, a convergence of studies has revealed why its effects appear so robust. Across many age-related diseases, cells exhibit a strikingly similar profile: growth and biosynthetic programs remain chronically active, as if locked in a state of metabolic overdrive. Viewed through this lens, aging is not simply the passive accumulation of molecular damage. Rather, many age-associated changes arise from growth-promoting programs that continue to run long after their original developmental purpose has been fulfilled.

Chief among these programs is the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), a master regulatory pathway that allows cells to sense their environment and decide how to allocate resources for growth and the conservation of energy. At a cellular level, mTOR integrates signals about nutrient availability, energy status, growth factors, and stress, and uses that information to determine whether a cell should grow, divide, and build new proteins, or conserve resources for repair and survival [2]. When nutrients are abundant, mTOR activity rises, directing cells toward growth by stimulating protein synthesis and anabolic metabolism. This function is indispensable during development, when rapid growth and tissue expansion are essential.

When nutrients are scarce, mTOR activity normally falls, allowing cells to shift away from growth and toward autophagy. Autophagy is a tightly regulated process by which cells break down damaged proteins and recycle worn-out organelles to use specifically for energy. Its importance for longevity is paramount. It functions as the cell’s primary maintenance and quality-control system. By clearing molecular debris, dampening the release of pro-inflammatory signals, and preserving mitochondrial integrity, autophagy plays a central role in preserving the functional integrity of the cell over time. From a longevity perspective, the goal is not continuous autophagy, but periodic reactivation—brief “pulses” of cellular cleanup that relieve maladaptive growth pressure, while still allowing mTOR signaling to rebound when needed to support normal protein synthesis, repair, and tissue function.

In healthy biology, this growth–repair switch is dynamic: mTOR rises to support building, then recedes to permit cleanup and renewal through autophagy. When mTOR is suppressed, either pharmacologically or through fasting, autophagy is stimulated. Conversely, when nutrients and anabolic signals are abundant, mTOR activity increases, driving cellular growth while simultaneously suppressing autophagy. This reciprocal relationship allows cells to alternate between periods of construction and maintenance as conditions demand.

In early life, mTOR activity is indispensable. mTOR signaling functions as a biological accelerator pedal—fueling growth, tissue expansion, and rapid repair during development and reproduction. But once development is complete, that accelerator does not seem to fully release. This pushes cells toward growth even when growth is no longer adaptive. At the same time, autophagy becomes progressively blunted, leaving cells unable to adequately clear damage.

This persistent growth bias has wide-ranging consequences. Cells remain locked in a growth-oriented state, driving continuous protein synthesis while suppressing autophagy. Damaged proteins and dysfunctional mitochondria accumulate, inflammatory signaling intensifies, and metabolic efficiency declines. Compounding this effect, mTOR activity remains abnormally elevated in senescent cells—cells that have exited the cell cycle but resist clearance. Although senescent cells no longer contribute to normal tissue function, they remain metabolically active and secrete a potent mix of pro-inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and matrix-degrading enzymes. Over time, the accumulation of these dysfunctional yet inflammatory cells promotes fibrosis, tissue degeneration, and chronic low-grade inflammation—hallmarks that collectively shape the physiology of aging.

Viewed through this lens, aging reflects not a passive breakdown of biological systems, but an active imbalance between growth and maintenance. This framework helps explain why mTOR dysregulation appears repeatedly across age-related disease states. From neurodegeneration and cardiomyopathy to immune dysfunction, reproductive aging, and cancer biology, excessive mTOR signaling emerges as a shared upstream driver rather than a downstream consequence.

In early life, mTOR activity is indispensable. mTOR signaling functions as a biological accelerator pedal—fueling growth, tissue expansion, and rapid repair during development and reproduction. But once development is complete, that accelerator does not seem to fully release. This pushes cells toward growth even when growth is no longer adaptive. At the same time, autophagy becomes progressively blunted, leaving cells unable to adequately clear damage.

We have explored these connections extensively:

If aging is driven, at least in part, by growth programs locked in a state of metabolic growth overdrive while cellular quality-control systems such as autophagy gradually decline, then rapamycin exerts its protective effects by easing pressure on this biological accelerator. Through selective inhibition of mTOR, rapamycin shifts cells away from perpetual growth and stimulates pulses of autophagy [2].

However, dosing is the critical component to capturing the geroprotective benefits of rapamycin. The effects of rapamycin are not binary but graded, emerging only within specific ranges of dose and exposure, making how rapamycin is used as important as whether it is used at all.

Why?

This distinction matters because mTOR does not operate as a single switch. It functions through two related but functionally distinct signaling complexes: mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2). These two complexes govern different functions and have very different sensitivities to rapamycin itself.

mTORC1 is the primary driver of growth-related processes. It stimulates protein synthesis, suppresses autophagy, and promotes anabolic metabolism in response to nutrient abundance. When we said earlier that mTOR tends to be locked in a growth mode as we age, we are specifically talking about mTORC1. This overactivity is closely linked to many hallmarks of aging and is the primary target of rapamycin’s geroprotective effects.

mTORC2, by contrast, plays a more foundational role in metabolic regulation and regulating immune function. It supports insulin signaling, glucose uptake, lipid metabolism, cytoskeletal organization, and cellular survival pathways. The inhibition of mTORC2 leads to a number of side effects we want to avoid when dosing rapamycin for longevity purposes.

This difference in function is matched by a difference in sensitivity to rapamycin. mTORC1 is acutely sensitive to rapamycin inhibition, particularly under conditions of intermittent or low-dose exposure. mTORC2, in contrast, is relatively resistant to rapamycin and is typically affected only under conditions of sustained, high-dose, or chronic administration.

This separation creates a narrow but meaningful therapeutic window: it allows mTORC1-driven growth signals to be selectively dampened—reactivating autophagy and cellular maintenance—while largely preserving the metabolic and immune functions governed by mTORC2.

From a longevity perspective, this distinction is critical. Intermittent, low-dose rapamycin is not intended to shut down mTOR signaling wholesale, but to recalibrate it—easing chronic growth pressure without destabilizing glucose regulation, insulin sensitivity, or immune function. When rapamycin exposure is too frequent or too high, that selectivity erodes, and mTORC2 inhibition begins to emerge, increasing the risk of metabolic side effects that undermine the healthspan goal—specifically compromising immune function and elevating metabolic markers.

This gives you some idea of how rapamycin is used for transplant patients. Rapamycin is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for indications such as immunosuppression in organ transplant recipients, certain seizure disorders, and has been investigated as an adjuvant therapy in oncology [3]. In these settings, dosing is typically daily—often ≥1 mg per day—designed to achieve sustained suppression of immune or proliferative activity through the chronic inhibition of mTOR signaling. These therapeutic objectives are fundamentally different from those pursued in longevity medicine.

In transplant and oncology contexts, this dosing strategy is intentional. Chronic daily exposure is used precisely because prolonged rapamycin administration can disrupt mTORC2 signaling, dampening immune cell activation, proliferation, and survival pathways that would otherwise promote graft rejection or tumor growth. In other words, what is considered a side effect in longevity applications, mTORC2 inhibition, is often the desired mechanism in immunosuppressive or anti-proliferative therapy. This clinical precedent helps explain why rapamycin has historically been viewed through the lens of immune suppression, even though its biological effects at lower, intermittent exposures occupy a very different mechanistic space.

In this light, dosing strategy becomes inseparable from mechanism. The question is no longer whether rapamycin inhibits mTOR, but how much, how often, and for how long—variables that determine whether rapamycin functions as a geroprotective modulator or as a blunt immunosuppressive agent.

In this light, dosing strategy becomes inseparable from mechanism. The question is no longer whether rapamycin inhibits mTOR, but how much, how often, and for how long—variables that determine whether rapamycin functions as a geroprotective modulator or as a blunt immunosuppressive agent.

If rapamycin’s promise lies in selectively dialing down mTOR signaling rather than shutting it off entirely, then dose and timing become the primary levers governing benefit versus risk. The challenge is that rapamycin’s most compelling longevity data have historically come from animal models, where exposure levels, metabolism, and dosing schedules differ substantially from those used in humans. Translating these findings therefore requires more than simple milligram conversion.

Bridging species remains essential. Mouse studies establish what is biologically possible, while companion dog trials—most notably those conducted through the Dog Aging Project—have provided a crucial intermediate step, offering pharmacokinetic and safety data in a long-lived mammal that shares human environments, disease patterns, and aging trajectories.

That translational gap is now, however, beginning to narrow. In 2025, new human clinical trials were published that directly inform how rapamycin behaves at low, intermittent doses in adults—providing the most concrete guidance to date on safety, tolerability, and biologically active exposure ranges. While none were designed to measure lifespan directly, these studies offer critical insight into dosing schedules, circulating drug levels, and downstream physiological effects relevant to healthspan. When viewed together with contemporary human trial data, these lines of evidence now allow rapamycin dosing to be framed in terms of relative exposure, timing, and physiological response, rather than fixed prescriptions or one-size-fits-all milligram targets.

In the sections that follow, we examine how rapamycin doses used in mice and dogs translate to humans, how recent human trials refine the lower and upper bounds of effective dosing, and why weekly, weight-adjusted schedules have emerged as a focal strategy. Understanding rapamycin’s role in longevity, ultimately, is less about identifying a single “correct” dose and more about learning how to modulate a powerful aging pathway with precision—using dose as a lever, not a blunt instrument.

Relative Rapamycin Dosing From Mice and Dogs to Humans

Animal Rapamycin Dose Translation

Determining an appropriate rapamycin dose for human longevity does not begin in the clinic, it begins with comparative biology. Much of what we know about rapamycin’s geroprotective potential originates from rodent studies, where lifespan extension has been repeatedly demonstrated using rapamycin delivered chronically in food. In these experiments, circulating rapamycin levels are often substantially higher than those typically targeted in human longevity applications. While effective for extending lifespan in mice, such exposure profiles are not directly transferable to humans, particularly when long-term safety is a priority.

Importantly, rodent studies reinforce that how rapamycin is delivered matters as much as how much is delivered. Intermittent dosing schedules, including once-weekly exposure, can reproduce many of the beneficial effects seen with continuous administration, while reducing adverse metabolic consequences associated with chronic mTOR inhibition. These findings carry two key translational implications: first, that absolute weekly dose is more relevant than daily intake, and second, that the temporal pattern of mTOR inhibition may be a critical determinant of benefit versus risk, depending on the clinical goal.

While mice establish what is biologically possible, they are a limited guide for human dosing. The Dog Aging Project (DAP) has been the key translational bridge. Early DAP pharmacokinetic studies deliberately employed very low doses of rapamycin—such as 0.025 mg/kg administered three times per week—not to test efficacy, but to answer a more basic question: could measurable circulating rapamycin levels be achieved safely in aging dogs [5, 6]? These studies demonstrated that even low-dose exposure was detectable and well tolerated, laying the groundwork for subsequent interventional trials for efficacy.

Building on this foundation, a masked randomized clinical trial in 17 companion dogs tested low-dose rapamycin and demonstrated short-term improvements in cardiac function alongside a favorable safety profile. These results informed the design of the larger TRIAD trial, which represented the first attempt to systematically test rapamycin dosing for aging-related outcomes in dogs over a longer time horizon [7, 8].

For TRIAD, investigators ultimately selected 0.15 mg/kg administered once weekly as the treatment dose. This decision was guided by three converging considerations:

- Rodent data identifying exposure ranges associated with biological benefit;

- Pharmacokinetic modeling from canine studies demonstrating tolerability and sustained exposure;

- The goal of achieving partial mTORC1 inhibition while minimizing immunosuppressive risk through mTORC2 inhibition.

Crucially, this work also clarified a lower-bound anchor for human exploration. A once-weekly dose of 0.075 mg/kg can be conservatively extrapolated from the earlier 0.025 mg/kg, three-times-weekly canine regimen, preserving total weekly exposure while simplifying dosing and reducing cumulative suppression. Although pharmacokinetics differ across species, this relative dosing framework provides a rational starting point for low-dose rapamycin in humans, one grounded not in arbitrary milligram selection, but in a stepwise translational logic.

Relative Rapamycin (0.075 mg/kg - 0.15 mg/kg) in Humans

Once rapamycin dosing is framed in relative, bodyweight-adjusted terms, the next challenge is translating that framework into practical human use. In humans, dose–response relationships are shaped not only by molecular targets, but also by body size, tissue distribution, and individual variability in drug metabolism. As a result, absolute milligram dosing must be interpreted through the lens of relative exposure rather than viewed as a one-size-fits-all prescription.

Using the translational range established from animal models, a relative dose of 0.075–0.15 mg/kg administered once weekly provides a useful starting point for human exploration. For a 70 kg adult, this corresponds roughly to 5–10 mg once weekly. For larger individuals—for example, those weighing closer to 100 kg—a higher absolute dose may be required to achieve comparable biological engagement of mTORC1 and downstream effects on autophagy, inflammation, and cellular senescence.

At the same time, human experience to date suggests that the effective longevity window is relatively broad. For the majority of adults, an absolute weekly dose in the range of 3–10 mg appears sufficient to engage aging-related pathways while maintaining a favorable safety profile in off-label, low-dose contexts [4]. Doses below this range may fail to meaningfully influence mTOR signaling, while doses substantially above it risk drifting toward exposure profiles associated with immunosuppressive use.

Importantly, these ranges should be understood as anchors rather than endpoints. Body weight offers a useful first approximation, but it does not capture differences in body composition, hepatic metabolism, or drug sensitivity that can meaningfully alter circulating rapamycin levels. As with other pathway-modulating therapies, optimal dosing is best viewed as a process of informed titration—guided by relative dose, clinical context, and ongoing assessment—rather than a fixed numerical target.

Relative bodyweight-based dosing scaling is only a first step as it does not account for individual variation in liver function, fat mass, drug sensitivity, or polypharmacy that may overlap with CYP3A4 or P-glycoprotein pathways necessary for rapamycin metabolism [2,3]. Despite impressive safety data, individual differences associated with rapamycin are best captured in routine lab follow ups with clinical oversight. In this context, rapamycin functions less like a blunt instrument and more like a volume control, which may be dialed carefully to influence aging biology without shutting down essential immune function.

2025 was an impressive year as important human trials were published [9,11]. In the following section, we will review what these human trials tell us about how to rapamycin to promote healthspan and its safety profile.

Clinical Rapamycin Data

Anti-Aging Benefits of Low Dose Rapamycin

Understanding rapamycin’s potential as a geroprotective agent requires moving beyond lifespan statistics and into the biology of aging itself. At its core, rapamycin acts on the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), a central signaling node that integrates information about nutrient availability, growth signals, and cellular stress. Targeting mTOR activity is necessary to prevent chronic overactivation associated with aging which is increasingly influenced by modern environments, characterized by constant nutrient abundance and low physical stress, which accelerate many hallmarks of aging [1,3]. Rapamycin’s relevance to longevity lies not in shutting this system down, but in periodically restoring balance to pathways that have drifted toward persistent growth signaling.

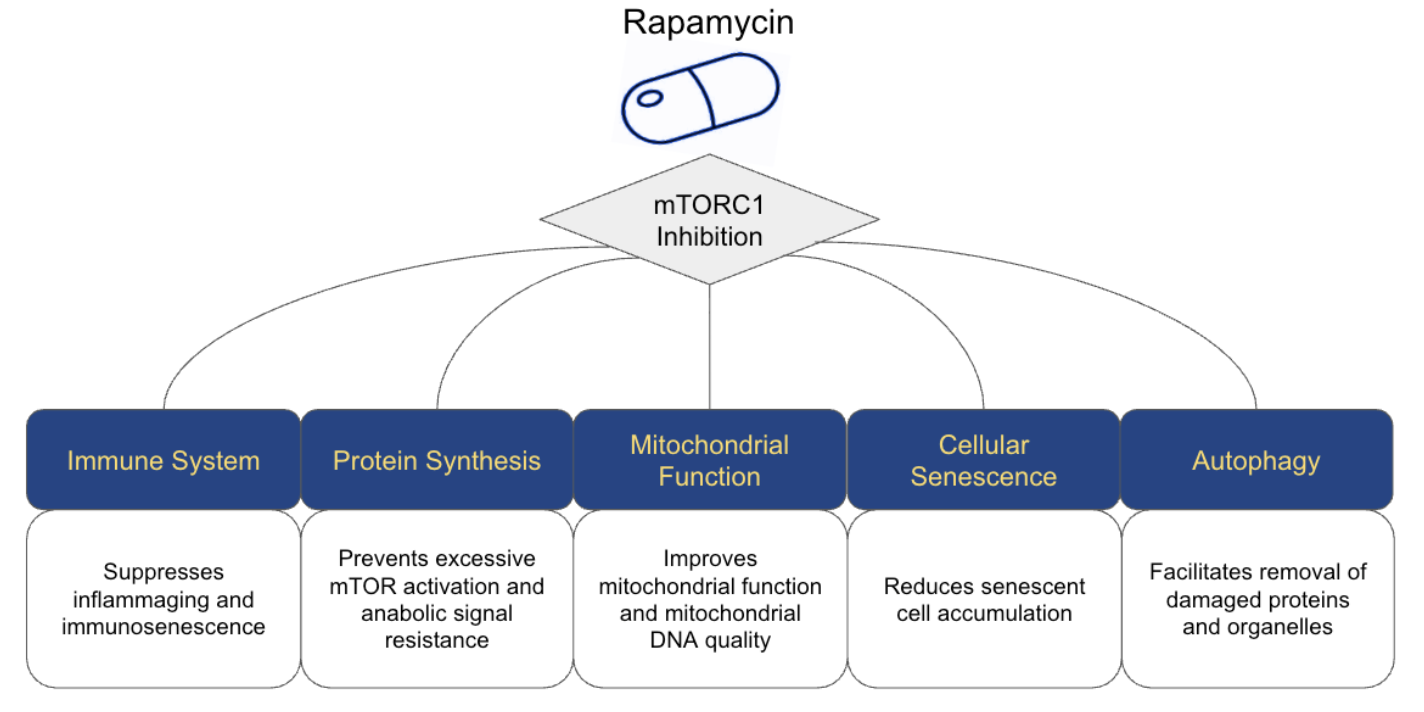

When applied at low, intermittent doses, rapamycin appears capable of influencing healthy aging processes for the better. This includes recalibrating immune function, tempering excessive protein synthesis in favor of maintenance and repair, improving mitochondrial efficiency, and enhancing the cell’s capacity for quality control through autophagy [1, 3, 12]. By acting upstream at mTOR, a shared regulatory hub, rapamycin offers a biologically potent pathway influencing multiple key areas of healthy aging simultaneously (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Rapamycin Primary Mechanisms for Anti-Aging Benefits

The PEARL Trial

The PEARL trial (Participatory Evaluation of Aging with Rapamycin for Longevity) is the first long-duration, placebo-controlled study to test weekly low-dose rapamycin in otherwise healthy middle-aged and older adults [9]. Participants were randomized to placebo or one of several weekly rapamycin doses over ~48 weeks [9].

Although the compounded preparation used was roughly 3-fold lower bioavailability [9,10] than generic sirolimus, the study still showed:

- Good overall tolerability, with serious adverse events similar to placebo;

- Modest improvements in selected physical and emotional well-being measures;

- No dramatic changes in major metabolic markers, but helpful safety data on low dose once weekly rapamycin.

From a dosing perspective, PEARL is crucial: it supports the idea that intermittent, low-dose weekly rapamycin is safe in older adults 50 to 85 years old. Although The primary outcome, visceral adiposity, did not differ significantly between groups. In women taking the higher 10 mg dose, there was a significant 6% increase in lean mass from baseline at 48 weeks [9]. There were also self-reported improvements in pain, emotional well-being, and general health [9].

Age, Organ Function, Polypharmacy and Comorbidities

Older adults often present with physiological and clinical factors that complicate rapamycin dosing, including reduced renal and hepatic clearance, polypharmacy, and elevated baseline risk for infections and metabolic disturbances.

Given rapamycin’s relatively narrow therapeutic window in traditional clinical indications, even low weekly doses may accumulate or interact unpredictably when drug clearance is impaired. This pharmacologic reality underlies the growing preference for “start low, go slow” titration strategies, even when targeting the commonly discussed longevity dosing range of 0.075–0.15 mg/kg.

In practice, once-weekly dosing of 3–6 mg or biweekly dosing is often discussed in longevity-focused settings [20]. Pharmacokinetic estimates suggest that rapamycin exerts biological effects at circulating levels around, or above, 5 ng/mL, with a higher likelihood of adverse effects above 20 ng/mL [21]. These nuances reinforce the need for personalized risk stratification, rather than a one-size-fits-all dosing approach, when considering rapamycin for healthspan applications.

Early Human Evidence from Rapalogs and Immune Function

Additional support for low-dose mTOR inhibition emerged from earlier work by Mannick et al. 2014, who examined the effects of everolimus (RAD001), a selective mTORC1 rapalog on immune function in older adults [17]. In this randomized study, low-dose everolimus administered at 0.5 mg/day or 5 mg weekly led to a ~20% increase in immune response titers following vaccination. The 5mg weekly dose for 6 weeks was found to boost influenza vaccine response in otherwise healthy older adults without significant side effects [17]. At the same time, circulating levels of PD-1–positive CD4 and CD8 T cells declined relative to placebo, a shift consistent with improved T-cell function and a more youthful immune phenotype.

Taken together, emerging human data suggest that low-dose mTOR inhibition occupies a biologically distinct zone between immune suppression and immune support. The early studies on rapalogs like everolimus reinforce the concept of a dose-dependent “sweet spot”, where geroprotective effects may emerge without overt immunosuppression. At the same time, a substantial gap remains between transplant-level daily dosing and the low, intermittent regimens now being explored for longevity, leaving many practical questions about optimal relative dosing open for investigation.

Real-world data from Matt Kaeberlein's lab, published in 2023, further support this framework, reporting lower rates of COVID infection and long-COVID among 333 individuals using rapamycin for healthspan extension, along with subjective improvements in well-being and physical stamina [18]. Importantly, these findings challenged the assumption that mTOR inhibition is inherently immunosuppressive. Instead, at low doses, mTORC1 inhibition appeared to enhance immune resilience, providing early human evidence that carefully titrated rapamycin exposure may improve, rather than impair, aspects of immune aging.

Rapamycin and Ovarian Aging: A 2025 Human Trial Clarifies Dose, Duration, and Biological Effect

One of the most informative human rapamycin studies published in 2025 examined its effects on age-related ovarian dysfunction and infertility. In a randomized controlled clinical trial reported in Cell Reports Medicine, Li and colleagues investigated whether short-term rapamycin treatment could reverse molecular features of ovarian aging and improve fertility outcomes in women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) [24].

The biological premise of the study was strikingly aligned with modern geroscience. Using integrated single-cell transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteostasis analyses, the authors identified ribosome dysregulation and excessive protein translation as a previously underappreciated hallmark of ovarian aging. Beginning in the mid-thirties, both oocytes and their surrounding cumulus cells showed a marked upregulation of ribosome-associated genes, accompanied by impaired lysosomal activity, accumulation of misfolded protein aggregates, and suppression of autophagy.

In effect, aging ovarian tissue appeared locked in a state of metabolic and anabolic overdrive—continuing to prioritize growth-like protein synthesis even as the cellular systems responsible for maintenance, recycling, and quality control progressively declined. This imbalance mirrors what has been observed across aging tissues more broadly and represents precisely the type of growth-maintenance mismatch that chronic mTORC1 signaling is known to enforce.

For the purposes of this review, the ovarian aging dynamics are representative of a phenomena that is happening across all cell types as we age: the cells enter in chronic metabolic overdrive, and their capacity to maintain quality control diminishes as autophagy function diminishes.

To test whether easing pressure on this overactive growth program could restore cellular balance and improve clinical outcomes, the investigators administered oral rapamycin at a dose of 1 mg daily for 21–28 days prior to oocyte retrieval. This regimen was intentionally short-term and tightly time-limited, targeting a narrow window of follicular maturation rather than imposing prolonged systemic exposure. Importantly, while well below transplant-level immunosuppressive dosing, this intervention was sufficient to measurably inhibit mTORC1 signaling [24].

The clinical effects were notable. Compared with controls, women receiving rapamycin produced significantly more high-quality embryos, demonstrated improved blastocyst development, and achieved higher clinical pregnancy rates. Among patients undergoing day 5–6 blastocyst transfer, pregnancy rates were more than threefold higher in the rapamycin group. Crucially, live birth rates were not reduced, providing early reassurance that short-term modulation of mTOR signaling did not impair downstream fetal development or obstetric outcomes in this context [24].

From a dosing perspective, the study offers several important lessons. First, it demonstrates that meaningful biological and functional effects can be achieved with low absolute doses when rapamycin is applied at the right time and for the right duration. Second, it underscores that duration matters as much as dose: a brief intervention was sufficient to relieve anabolic overdrive, restore proteostasis, and improve function without inducing systemic toxicity. Third, it reinforces a central theme emerging across human rapamycin studies—that benefits arise not from maximal pathway suppression, but from partial, context-specific mTORC1 modulation.

Equally important are the safety implications. Despite acting on a pathway traditionally associated with immunosuppression, no increase in adverse clinical outcomes was observed over the treatment period. This aligns with a growing body of evidence suggesting that low-dose, time-limited rapamycin occupies a distinct biological zone, separate from chronic immunosuppressive use and characterized instead by restoration of cellular balance.

Taken together, this ovarian aging trial provides one of the clearest human demonstrations to date that rapamycin dosing can be both biologically potent and clinically tolerable when applied thoughtfully. While the study does not establish long-term healthspan effects, it offers a critical proof of principle: relieving age-related metabolic overdrive—rather than suppressing biology wholesale—can reverse molecular dysfunction and translate into meaningful functional gains in humans.

What This Study Teaches Us About Rapamycin Dosing

- Biological Engagement at Low Dose: The 1 mg daily dose — modest by transplant or oncology standards — was sufficient to engage mTORC1 biology in human ovarian tissue, shifting molecular profiles toward improved proteostasis and cellular repair within a few weeks.

- Timing Matters as Much as Dose: Because ovarian cycles are tightly phased, applying rapamycin during the follicular development window allowed targeted modulation of growth versus maintenance signals precisely when eggs and support cells are most sensitive to metabolic imbalance.

- Safety Can Be Preserved with Short Exposure: Although chronic mTOR inhibition carries immunosuppressive risk, short, focused exposure at this level did not increase adverse clinical or embryologic outcomes. This mirrors patterns seen in other low-dose human studies, where intermittent or time-limited dosing occupies a distinct, tolerable biological space.

- Mechanism Links to Function: The trial not only measured clinical outcomes but also integrated mechanistic insight — linking improved embryo quality to the underlying rebalance of translation and autophagy in ovarian support cells. This bridges the physiology of aging with tangible reproductive endpoints.

Rapamycin and ME/CFS: Weekly Low-Dose mTOR Inhibition as a Test of Mechanism and Tolerability

A second influential human study published in 2025 examined rapamycin in the context of myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), a debilitating condition defined by profound fatigue, post-exertional malaise (PEM), sleep disruption, and autonomic dysfunction. Increasingly, ME/CFS is being understood not as a disorder of motivation or conditioning, but as a breakdown in the body’s ability to recover after exertion. In a large, decentralized observational study, Ruan and colleagues tested whether weekly low-dose rapamycin could relieve core symptoms of ME/CFS by restoring normal cellular maintenance processes [26].

The biological rationale for the study was unusually clear. Earlier work from the same group suggested that ME/CFS may arise, in part, from a failure of cells to switch out of a high-activity, growth-oriented state after physical or mental stress. Under normal conditions, exertion is followed by a coordinated shift toward repair: damaged proteins are cleared, energy systems reset, and inflammation resolves. In ME/CFS, that transition appears to be impaired. Cells remain metabolically “on,” but their cleanup and recovery systems lag behind—a mismatch that may help explain why even mild exertion can trigger prolonged symptom flare-ups.

At the center of this failure is the disruption of autophagy. In patients with ME/CFS, the investigators consistently observed elevated levels of an inactive form of a protein required to initiate autophagy. When growth-promoting signals remain overactive, this protein is chemically modified in a way that prevents autophagy from starting. As a result, cellular debris accumulates and recovery stalls. The presence of this inactive marker in the bloodstream suggested that impaired cellular recovery was not merely a downstream effect of illness, but a core driver of symptoms, particularly post-exertional malaise [26].

To test whether mTOR inhibition could reverse this defect, the investigators administered rapamycin at a dose of 6 mg once weekly. The study enrolled 86 patients across six U.S. clinical centers, with 40 participants completing the full 90-day protocol. Importantly, this dosing schedule falls squarely within the low-dose, intermittent range increasingly discussed for longevity applications, rather than transplant-level immunosuppression [26].

From a safety standpoint, the findings were reassuring. Weekly rapamycin was well tolerated, with no serious adverse events reported. Transient symptoms such as mild gastrointestinal discomfort, headache, or insomnia occurred primarily early in treatment and declined over time. Crucially, no clinically significant abnormalities emerged in safety laboratory panels, including metabolic markers, blood counts, or inflammatory indices—an important distinction from the dyslipidemia, cytopenias, and insulin resistance seen with higher daily dosing in other contexts [26].

Clinically, the improvements were substantial. Across multiple validated patient-reported outcome measures participants experienced progressive and statistically significant reductions in fatigue, PEM, sleep disturbance, and orthostatic intolerance over the 90-day period. These were not transient effects: symptom relief tended to strengthen with continued weekly dosing, consistent with gradual restoration of cellular recovery capacity rather than acute symptom suppression [26].

In parallel, blood samples were collected to examine whether clinical changes were accompanied by shifts in autophagy-related signaling. Rather than surveying hundreds of molecular markers, the investigators focused on two biologically grounded indicators that reflect different steps of the cellular recycling process. BECLIN-1 is a protein required to initiate the formation of autophagosomes—the temporary structures that enclose damaged cellular components so they can be broken down and reused. Phosphorylated ATG13, by contrast, represents a “switched-off” state of an early autophagy protein; when ATG13 is phosphorylated by mTOR, the recycling process is blocked before it can begin.

By tracking both a marker of autophagy initiation and a marker of autophagy inhibition, the researchers could assess not only whether the cleanup machinery was being assembled, but whether it was being allowed to operate. Together, these markers offered a practical window into whether rapamycin was engaging its intended target pathway in living patients.

Several dosing insights emerge from this work. First, 6 mg once weekly was sufficient to meaningfully alter recovery biology in humans, even in a heterogeneous and chronically ill population. Second, benefits accumulated over time, suggesting that sustained—but still intermittent—exposure is required to unwind long-standing metabolic overdrive. Third, the absence of immunosuppressive complications reinforces the idea that weekly low-dose rapamycin occupies a distinct biological zone, one focused on restoring balance rather than suppressing function.

The study also highlighted heterogeneity in response. Patients with a documented post-infectious onset of ME/CFS showed the most pronounced improvements, raising the possibility that a subset of patients are particularly sensitive to growth-repair imbalance driven by chronic immune activation. This observation echoes a broader theme emerging across rapamycin studies: dose matters, but biological context matters just as much.

Additional Clinical Trials Focused on Anti-Aging

Prior to the PEARL trial, several small clinical studies and open-label investigations explored the effects of low-dose rapamycin or rapalogs in older adults, helping to establish early safety signals and guide subsequent dosing strategies. These trials typically employed more frequent dosing regimens, ranging from 0.5 mg to 2 mg daily for short durations, and focused on biomarkers of immune function, physical health, and aging-related physiology [12].

Muscle Health and Age-Related Loss

One area of particular interest is skeletal muscle preservation. Sarcopenia has been repeatedly associated with frailty, disability, and adverse health outcomes in aging populations [13]. While mTOR signaling is classically linked to muscle protein synthesis, emerging evidence suggests that the relationship between mTOR activity and muscle health may be age-dependent and that excess activation of mTOR may contribute to age-related resistance to anabolic stimuli like amino acids [14]. In this context, sirolimus may exert anti-sarcopenic effects not by maximizing acute protein synthesis, but by reducing excessive catabolic signaling and improving maintenance, or even increasing muscle mass over time, as in the PEARL Trial [9]. This raises the possibility that partial mTOR inhibition could support muscle preservation through mechanisms distinct from those targeted by traditional anabolic interventions.

Daily Low-Dose Rapamycin (1 mg/day)

One of the most detailed early trials of low-dose rapamycin in healthy older adults was conducted by Kraig and colleagues, at the University of Texas, who evaluated the safety of 1 mg/day sirolimus administered continuously for eight weeks in 25 participants aged 70–95 years [15]. This regimen produced a mean circulating sirolimus level of 7.2 ng/dL, and was associated with measurable changes across hematologic, hormonal, and physical parameters [15]. Notably, the study identified no significant adverse clinical outcomes over the short intervention period.

The authors acknowledged two primary limitations: the relatively short duration of the study and the use of continuous daily dosing, rather than intermittent schedules that may better align with longevity goals and reduce off-target effects. Despite these constraints, one particularly interesting finding was a significant reduction in red cell distribution width (RDW), a biomarker that has been associated with biological aging and mortality risk. Lower RDW values are often interpreted as reflecting a more “youthful” hematological profile, suggesting potential healthy aging benefits for red blood cells [16].

Now that we have discussed some of the preclinical and clinical trials of rapamycin, let’s explore the application of these data points to help create a framework on how to dose rapamycin for healthspan-promoting purposes.

Taken together, these preclinical and human studies converge on a central insight: rapamycin’s benefits are real, but they are highly contingent on how the drug is used. Across reproductive, cardiovascular, and metabolic contexts, meaningful effects emerged not from maximal inhibition, but from precise dosing. With that foundation in place, the critical question becomes how to translate these data into practical dosing frameworks for healthspan-focused use. The sections that follow explore the key variables that shape rapamycin exposure in humans—including body size, age, metabolic context, and comorbid conditions—and why these factors complicate any one-size-fits-all approach to dosing.

Dosing Nuances: Body Size, Age, and Condition

Body Size and Composition

Most pharmacologists favor weight-based dosing (mg/kg) as a practical way to approximate how much drug is required to achieve a given plasma exposure. Under this framework, larger individuals typically require higher absolute doses to reach blood concentrations comparable to those seen in smaller individuals. This approach is widely used in both clinical medicine and translational research, and it provides a useful starting point for thinking about rapamycin dosing in heterogeneous populations.

However, rapamycin’s pharmacokinetics are unique. Unlike many water-soluble drugs, rapamycin is highly lipophilic, meaning its distribution throughout the body is influenced not only by total body mass, but also by tissue composition and cellular binding dynamics [10].

Rapamycin has unique pharmacokinetics among different humans because:

- It is highly lipophilic, distributing into tissues and associating with red blood cells

- Individuals with high adiposity may sequester more drug in fat compartments, potentially altering effective circulating exposure

- Conversely, leaner individuals may experience higher peak concentrations for the same mg/kg dose

These factors suggest that two individuals of identical body weight may experience meaningfully different exposures, depending on their sex, relative proportions of lean mass, adipose tissue, and blood volume [10,19]. In individuals with higher body fat, greater tissue sequestration could blunt peak plasma levels, while in leaner individuals the same dose could result in higher transient exposure potentially increasing both biological effect and side-effect risk.

Taken together, these considerations indicate that simple mg/kg scaling may over- or under-estimate optimal dosing at the extremes of body composition, particularly in people with very high or very low BMI. For example, individuals with higher body adiposity and BMI would likely use a body weight adjustment in order to improve relative dose calculations.

As the field matures, future clinical trials will likely need to move beyond body weight alone and examine dose-response relationships stratified by body composition as well as biological sex, allowing for more precise and individualized approaches to rapamycin dosing in the context of healthy aging.

Age, Organ Function, Polypharmacy and Comorbidities

Older adults often present with physiological and clinical factors that complicate rapamycin dosing, including reduced renal and hepatic clearance, polypharmacy, and elevated baseline risk for infections and metabolic disturbances.

Given rapamycin’s relatively narrow therapeutic window in traditional clinical indications, even low weekly doses may accumulate or interact unpredictably when drug clearance is impaired. This pharmacologic reality underlies the growing preference for “start low, go slow” titration strategies, even when targeting the commonly discussed longevity dosing range of 0.075–0.15 mg/kg.

In practice, once-weekly dosing of 3–6 mg or biweekly dosing is often discussed in longevity-focused settings [20]. Pharmacokinetic estimates suggest that rapamycin exerts biological effects at circulating levels around, or above, 5 ng/mL, with a higher likelihood of adverse effects above 20 ng/mL [21]. These nuances reinforce the need for personalized risk stratification, rather than a one-size-fits-all dosing approach, when considering rapamycin for healthspan applications.

The Case for Intermittent Rapamycin Dosing

A recurring theme across rapamycin studies is that many human trials have relied on daily low-dose administration, often around 1 mg per day. These regimens were selected for practical reasons: ease of adherence, predictable pharmacokinetics, and historical precedent from clinical use. Yet when viewed through the lens of aging biology, daily exposure may not be the most biologically aligned strategy for promoting long-term healthspan.

From a longevity perspective, the objective is not continuous suppression of mTOR signaling, but periodic rebalancing. Aging appears to be driven, in part, by growth programs that remain chronically engaged while cellular maintenance systems such as autophagy become progressively blunted. The therapeutic goal, therefore, is not to keep autophagy permanently elevated, but to reactivate it intermittently—providing discrete windows of cellular cleanup that relieve accumulated damage without impairing the growth and repair functions that tissues still require.

Intermittent dosing offers a theoretical advantage by leveraging the natural on–off dynamics of the mTOR–autophagy axis. Rapamycin exposure temporarily suppresses mTORC1 activity, allowing autophagy to engage. As drug levels fall between doses, mTOR signaling can recover, permitting normal protein synthesis, mitochondrial biogenesis, immune surveillance, and tissue repair to resume. In this framework, rapamycin functions less like a chronic inhibitor and more like a metabolic reset signal, nudging cells out of persistent growth mode and back toward balanced cycling between growth and maintenance.

Pharmacokinetics further support this approach. Rapamycin has a long half-life in humans, meaning that even a single weekly dose can sustain biologically meaningful mTORC1 inhibition for several days. Extending dosing intervals allows mTORC1 suppression to decay naturally, reducing cumulative pathway inhibition and potentially lowering the risk of off-target effects associated with sustained exposure—particularly unintended mTORC2 inhibition.

By contrast, daily dosing compresses these cycles. Even at low doses, repeated daily administration can lead to overlapping exposure windows, diminishing the depth of mTOR recovery between doses. While this may be appropriate for disease-specific indications, it may be less ideal for longevity applications where preserving physiological flexibility is paramount.

Importantly, intermittent dosing also mirrors evolutionary and physiological patterns. Throughout most of human history, periods of nutrient abundance were punctuated by fasting, illness, or physical stress—conditions that naturally suppressed mTOR and activated autophagy in pulses rather than continuously. Weekly or bi-weekly rapamycin dosing may therefore approximate this ancestral rhythm more closely than chronic daily exposure.

It is essential to emphasize that this framework is theory-driven and translational, rather than definitively proven. Direct head-to-head trials comparing daily versus intermittent rapamycin dosing for longevity outcomes have not yet been conducted. However, converging evidence from animal studies, companion dog trials, pharmacokinetic modeling, and early human data supports the plausibility that intermittent mTORC1 inhibition may capture much of rapamycin’s benefit while reducing long-term risk.

In this context, weekly or bi-weekly dosing represents an attempt to align rapamycin use with the underlying biology of aging—favoring pulses of autophagy and cellular reset over continuous suppression. Whether this strategy ultimately proves superior will require rigorous clinical testing, but it provides a coherent mechanistic rationale for how rapamycin might be used not merely to inhibit a pathway, but to restore balance within it.

Looking Ahead to Robust Low-Dose Human Clinical Trials

Despite promising research and enthusiasm among longevity enthusiasts, we do not yet have large, long-term trials that show low-dose rapamycin (e.g., 0.075–0.15 mg/kg weekly) definitively slows human aging, extends life, or prevents age-related disease in large human trials.

Current evidence is available in humans:

- Over the short- to medium-term duration (weeks, months, but not years)

- Focused on intermediate endpoints (biomarkers, functional tests, quality-of-life scales)

Reviews from translational geroscience groups repeatedly emphasize that the translational gap is still wide from mice to humans: while rapamycin robustly extends lifespan (15-36%) in mice, human data on lifespan is lacking. We are starting to see some early encouraging signals related to (A) the optimal dosing and dose schedules for humans, (B) which subgroups benefit most, or (C) how long treatment must be continued [1,3].

Rapamycin Human Research Trial Data to Watch For:

Several ongoing clinical trials are beginning to test whether rapamycin’s robust preclinical longevity signals can translate into measurable benefits in human aging and cognitive health.

Two ongoing studies are specifically focused on cognitive outcomes:

- The Evaluating Rapamycin Treatment in Alzheimer’s Disease using Positron Emission Tomography (ERAP) trial is a six-month, single-arm, open-label Phase IIa study administering 7 mg of rapamycin weekly and assessing changes in cerebral glucose metabolism using PET imaging, along with MRI-based structural measures [22].

- The Rapamycin – Effects on Alzheimer’s and Cognitive Health (REACH) trial is evaluating 1 mg of daily rapamycin and its impact on multiple biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease burden [23]. Together, these studies aim to determine whether rapamycin’s preclinical neuroprotective effects can be detected in vivo through imaging and biomarker endpoints in humans.

Beyond cognition, several additional trials are exploring rapamycin’s broader role in functional aging. These trials include:

- EVERLAST - The Everolimus Aging Study (NCT05835999)

- The Role of Sirolimus in Preventing Functional Decline in Older Adults (NCT05237687)

- Effect of Rapamycin in Ovarian Aging (NCT05836025).

While still early, these investigations collectively represent a meaningful shift toward rigorously testing rapamycin’s potential as a human gerotherapeutic, fueling optimism that mechanistic insights may soon be evaluated against clinically relevant, human, aging outcomes.

Practical and Ethical Considerations

Given this uncertainty, low-dose rapamycin for healthspan should be framed as experimental, best pursued within clinical trials or under careful, specialist supervision.

Key principles emerging from the current literature include:

- Intermittent dosing (weekly or less frequent) appears safer than chronic daily dosing for longevity goals.

- Weight-based thinking (mg/kg) is helpful, but should be refined by body composition, organ function, and concomitant drugs.

- Transparent communication about unknowns is essential; individuals should understand that healthspan dosing is not yet standard of care, and long-term risks and benefits remain uncertain.

Framing rapamycin use within these ethical and practical boundaries helps ensure that scientific curiosity does not outpace clinical responsibility, particularly as the field awaits more definitive human data.

Conclusion: Dose as the Lever, Evidence as the Limiter

Low-dose rapamycin roughly 0.075–0.15 mg/kg administered once weekly has emerged as a promising conceptual strategy for engaging mTOR-mediated longevity pathways without fully crossing into immunosuppressive territory. This dosing range is informed by converging evidence from animal studies (including rodents and especially dogs), pharmacokinetic modeling, and early human trials.

As additional data emerge from the exciting work underway in humans and next-generation clinical trials, it may become possible to define true minimum effective doses and upper safety thresholds across different body sizes, ages, and clinical backgrounds. In the interim consistent clinical partnership, routine lab work and communication enable relative dose optimization for individual human longevity enhancement.

- Konopka, A. R., Lamming, D. W., RAP PAC Investigators, & EVERLAST Investigators (2023). Blazing a trail for the clinical use of rapamycin as a geroprotecTOR. GeroScience, 45(5), 2769–2783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-00935-x

- Ryave, J., & Coleman, A. E. (2025). Rapamycin as a potential intervention to promote longevity and extend healthspan in companion dogs. Journal of Veterinary Science, 26(Suppl 1), S181–S198. https://doi.org/10.4142/jvs.25219

- Roark, K. M., & Iffland, P. H., 2nd (2025). Rapamycin for longevity: the pros, the cons, and future perspectives. Frontiers in aging, 6, 1628187. https://doi.org/10.3389/fragi.2025.1628187

- Hands, J. M., Lustgarten, M. S., Frame, L. A., & Rosen, B. (2025). What is the clinical evidence to support off-label rapamycin therapy in healthy adults?. Aging, 17(8), 2079–2088. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.206300

- Guelfi, G., Capaccia, C., Tedeschi, M., Bufalari, A., Leonardi, L., Cenci-Goga, B., & Maranesi, M. (2024). Dog Aging: A Comprehensive Review of Molecular, Cellular, and Physiological Processes. Cells, 13(24), 2101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13242101

- Evans, J. B., Morrison, A. J., Javors, M. A., Lopez-Cruzan, M., Promislow, D. E., Kaeberlein, M., & Creevy, K. E. (2021). Pharmacokinetics of long-term low-dose oral rapamycin in four healthy middle-aged companion dogs. bioRxiv, 2021-01.

- Barnett, B. G., Wesselowski, S. R., Gordon, S. G., Saunders, A. B., Promislow, D. E. L., Schwartz, S. M., Chou, L., Evans, J. B., Kaeberlein, M., & Creevy, K. E. (2023). A masked, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial evaluating safety and the effect on cardiac function of low-dose rapamycin in 17 healthy client-owned dogs. Frontiers in veterinary science, 10, 1168711. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1168711

- Coleman, A. E., Creevy, K. E., Anderson, R., Reed, M. J., Fajt, V. R., Aicher, K. M., Atiee, G., Barnett, B. G., Baumwart, R. D., Boudreau, B., Cunningham, S. M., Dunbar, M. D., Ditzler, B., Ferguson, A. M., Forsyth, K. K., Gambino, A. N., Gordon, S. G., Hammond, H. K., Holland, S. N., Iannaccone, M. K., … Dog Aging Project Consortium (2025). Test of Rapamycin in Aging Dogs (TRIAD): study design and rationale for a prospective, parallel-group, double-masked, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial of rapamycin in healthy middle-aged dogs from the Dog Aging Project. GeroScience, 47(3), 2851–2877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-024-01484-7

- Moel, M., Harinath, G., Lee, V., Nyquist, A., Morgan, S. L., Isman, A., & Zalzala, S. (2025). Influence of rapamycin on safety and healthspan metrics after one year: PEARL trial results. Aging, 17(4), 908–936. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.206235

- Harinath, G., Lee, V., Nyquist, A., Moel, M., Wouters, M., Hagemeier, J., ... & Zalzala, S. (2024). The bioavailability of compounded and generic rapamycin in normative aging individuals: A retrospective study and review with clinical implications. MedRxiv, 2024-08.

- Moody, A. J., Wu, Y., Romo, T. Q., Koek, W., Li, J., Linehan, L. A., Clarke, G. D., Yang, E. Y., Espinoza, S. E., Musi, N., Chilton, R. J., Kraig, E., & Kellogg, D. L., Jr (2025). Short-term mTOR inhibition by rapamycin improves cardiac and endothelial function in older men: a proof-of concept pilot study. GeroScience, 10.1007/s11357-025-01855-8. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-025-01855-8

- Sanati, M., Afshari, A. R., Aminyavari, S., Banach, M., & Sahebkar, A. (2024). Impact of rapamycin on longevity: updated insights. Arch Med Sci.

- Zhang, X., Wang, C., Dou, Q., Zhang, W., Yang, Y., & Xie, X. (2018). Sarcopenia as a predictor of all-cause mortality among older nursing home residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open, 8(11), e021252. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021252

- Yoon M. S. (2017). mTOR as a Key Regulator in Maintaining Skeletal Muscle Mass. Frontiers in physiology, 8, 788. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00788

- Kraig, E., Linehan, L. A., Liang, H., Romo, T. Q., Liu, Q., Wu, Y., Benavides, A. D., Curiel, T. J., Javors, M. A., Musi, N., Chiodo, L., Koek, W., Gelfond, J. A. L., & Kellogg, D. L., Jr (2018). A randomized control trial to establish the feasibility and safety of rapamycin treatment in an older human cohort: Immunological, physical performance, and cognitive effects. Experimental gerontology, 105, 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2017.12.026

- Kraig, E., Linehan, L. A., Liang, H., Romo, T. Q., Liu, Q., Wu, Y., Benavides, A. D., Curiel, T. J., Javors, M. A., Musi, N., Chiodo, L., Koek, W., Gelfond, J. A. L., & Kellogg, D. L., Jr (2018). A randomized control trial to establish the feasibility and safety of rapamycin treatment in an older human cohort: Immunological, physical performance, and cognitive effects. Experimental gerontology, 105, 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2017.12.026

- Mannick, J. B., Del Giudice, G., Lattanzi, M., Valiante, N. M., Praestgaard, J., Huang, B., Lonetto, M. A., Maecker, H. T., Kovarik, J., Carson, S., Glass, D. J., & Klickstein, L. B. (2014). mTOR inhibition improves immune function in the elderly. Science translational medicine, 6(268), 268ra179. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3009892

- Kaeberlein, T. L., Green, A. S., Haddad, G., Hudson, J., Isman, A., Nyquist, A., Rosen, B. S., Suh, Y., Zalzala, S., Zhang, X., Blagosklonny, M. V., An, J. Y., & Kaeberlein, M. (2023). Evaluation of off-label rapamycin use to promote healthspan in 333 adults. GeroScience, 45(5), 2757–2768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-00818-1

- Mannaa, M., Pfennigwerth, P., Fielitz, J., Gollasch, M., & Boschmann, M. (2023). Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition impacts energy homeostasis and induces sex-specific body weight loss in humans. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle, 14(6), 2757–2767. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13352

- Blagosklonny M. V. (2023). Towards disease-oriented dosing of rapamycin for longevity: does aging exist or only age-related diseases?. Aging, 15(14), 6632–6640. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.204920

- MacDonald, A., Scarola, J., Burke, J. T., & Zimmerman, J. J. (2000). Clinical pharmacokinetics and therapeutic drug monitoring of sirolimus. Clinical therapeutics, 22 Suppl B, B101–B121. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2918(00)89027-x

- Svensson, J. E., Bolin, M., Thor, D., Williams, P. A., Brautaset, R., Carlsson, M., Sörensson, P., Marlevi, D., Spin-Neto, R., Probst, M., Hagman, G., Morén, A. F., Kivipelto, M., & Plavén-Sigray, P. (2024). Evaluating the effect of rapamycin treatment in Alzheimer's disease and aging using in vivo imaging: the ERAP phase IIa clinical study protocol. BMC neurology, 24(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-024-03596-1

- Gonzales, M. M., Garbarino, V. R., Kautz, T. F., Song, X., Lopez-Cruzan, M., Linehan, L., Van Skike, C. E., De Erausquin, G. A., Galvan, V., Orr, M. E., Musi, N., He, Y., Bateman, R. J., Wang, C. P., Seshadri, S., Kraig, E., & Kellogg, D., Jr (2025). Rapamycin treatment for Alzheimer's disease and related dementias: a pilot phase 1 clinical trial. Communications medicine, 5(1), 189. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00904-9

- Li, Jie et al. Ribosome dysregulation and intervention in age-related infertility

Li, Jie et al.

Cell Reports Medicine, Volume 6, Issue 11, 102424 - Moody, A.J., Wu, Y., Romo, T.Q. et al. Short-term mTOR inhibition by rapamycin improves cardiac and endothelial function in older men: a proof-of concept pilot study. GeroScience (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-025-01855-8

- Ruan BT, Bulbule S, Reyes A, Chheda B, Bateman L, Bell J, Yellman B, Grach S, Berner J, Peterson DL, Kaufman D, Roy A, Gottschalk CG. Low Dose Rapamycin Alleviates Clinical Symptoms of Fatigue and PEM in ME/CFS Patients via Improvement of Autophagy. Res Sq [Preprint]. 2025 Jun 3:rs.3.rs-6596158. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-6596158/v1. Update in: J Transl Med. 2025 Oct 21;23(1):1148. doi: 10.1186/s12967-025-07213-8. PMID: 40502741; PMCID: PMC12155199. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-6596158/v1

Related studies