Exercise Modalities and Mitochondrial and Vascular Remodeling—Comparing Endurance, HIIT, and Sprint Interval Training

Prefer to listen? Hit play for a conversational, audio‑style summary of this article’s key points.

Exercise is a longevity intervention because it upgrades biological infrastructure. The strongest healthspan benefits come from strengthening two systems that age erodes: oxygen delivery through the vasculature and energy production through mitochondria.

VO₂max is more than a performance metric; it is a marker of physiological reserve. Higher aerobic fitness reflects better oxygen transport and extraction capacity and is strongly associated with lower all-cause mortality risk.

Mitochondria adapt quickly, especially when intensity is used strategically. High-intensity efforts create powerful metabolic signals that can rapidly stimulate mitochondrial remodeling, particularly early in training.

Capillary remodeling follows a different timeline than mitochondrial remodeling. Angiogenesis tends to occur early and may plateau, highlighting why sustained training and not just brief bursts matters for vascular durability.

Different exercise modalities drive different adaptations. Endurance training most reliably improves capillary density and aerobic foundation; HIIT provides time-efficient mitochondrial and VO₂max gains; sprint training delivers rapid mitochondrial signaling but can plateau; resistance training preserves strength and independence.

Time efficiency matters for real-world healthspan. The best training program is not the most extreme—it is the one that can be repeated consistently for years. Small, well-chosen doses can yield meaningful physiological returns.

For longevity, variety beats specialization. Combining aerobic training (endurance + intervals) with resistance training supports mitochondrial health, vascular function, and musculoskeletal resilience—the three pillars most strongly tied to aging well.

Importance of Mitochondrial and Vascular Function

Exercise training remains one of the most powerful interventions for extending healthspan. Few, if any, interventions have been validated as consistently across populations and influence as many biological systems simultaneously. Regular physical activity is associated with lower risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disease, several cancers [1,2,3], and all-cause mortality [3]. But the value of exercise is not limited to disease prevention. Higher fitness levels are reliably linked to greater day-to-day energy, better mobility, and longer preservation of physical independence traits that often distinguish healthspan extension [4,5,6]. This has driven decades of research aimed at identifying which physiological adaptations matter most for longevity and performance, and what the minimum effective dose of exercise might be to reliably produce them.

Although nearly every organ system adapts to training, two biological networks stand out as especially central: the vasculature and the mitochondria. Blood vessels determine how efficiently oxygen and nutrients are delivered throughout the body, while mitochondria convert those raw materials into usable cellular energy [7,8]. Together, they form the infrastructure of human performance, supporting everything from endurance and strength to cognitive stamina and metabolic stability. When vascular function and mitochondrial efficiency decline, as they often do with aging and prolonged inactivity, the consequences are measurable: reduced cardiovascular fitness, worsening metabolic health, loss of physical independence, and diminished quality of life [9,10,11].

However, the reverse is also true. Training that preserves or enhances vascular and mitochondrial function slows age-related declines, sustaining a more youthful physiological capacity across decades, not just for athletes, but for anyone seeking longevity enhancement.

In this research review, we examine the underlying physiology of the vascular system and mitochondria, and the distinct ways each adapts to different forms of exercise training. We then translate this biology into practical, evidence-based training strategies showing how exercise can be structured to optimize vascular and mitochondrial health across a wide range of goals, time constraints, and fitness levels. Finally, we identify the minimum effective training doses and explore when additional training yields meaningful returns, clarifying how to invest effort efficiently while maximizing long-term health benefits.

VO₂max: The Integrated Readout of Vascular and Mitochondrial Health

If the vasculature and mitochondria form the body’s energy infrastructure, then maximum oxygen uptake (VO₂max) is one of the cleanest ways to measure how well that infrastructure performs under exertional stress. VO₂max reflects the maximum rate at which the body can take in, transport, and use oxygen during intense exercise. When people engage in cardiovascular training, they are often trying to improve their body’s ability to use oxygen to make energy. In practical terms, VO₂max represents the upper limit of sustained aerobic energy production. Because oxygen is required for efficient, high-output ATP generation in mitochondria, VO₂max has become the gold-standard metric of aerobic fitness and one of the strongest predictors of long-term health, functional capacity, and successful aging [12].

The relationship between VO₂max and health is not subtle. Individuals with VO₂max values in the 75th percentile or higher show roughly a 3 to 5-fold reduction in all-cause mortality risk compared with those in the lowest quartile [12]. That association is so robust that VO₂max is increasingly viewed not merely as a performance metric, but as a healthspan vital sign reflecting the functional reserve of the cardiovascular and metabolic systems.

Mechanistically, VO₂max can be understood as the product of two fundamental processes:

- Cardiac Output: how much oxygen-rich blood the heart can pump to working tissues usually measured in liters per minute (L/min)

- Oxygen Extraction: how effectively those tissues pull oxygen out of the blood and use it in mitochondria.

The product of these two components, cardiac output and the arterial–venous oxygen difference (a-vO₂ diff), equals VO₂max. This is a measurement of the body’s maximum capacity to move oxygen from the atmosphere into the mitochondria where it ultimately powers cellular work (ie. exercise).

The relationship between VO₂max and health is not subtle. Individuals with VO₂max values in the 75th percentile or higher show roughly a 3 to 5-fold reduction in all-cause mortality risk compared with those in the lowest quartile

The Delivery Side: Cardiac Output and the Vascular Pipeline

Oxygen delivery begins with the heart. Cardiac output reflects how much blood the heart can pump per minute effectively the volume of oxygen transport capacity moving through the system. Because oxygen is carried primarily bound to hemoglobin, the more blood that circulates through active tissues, the more oxygen becomes available for metabolism.

The anatomical route is straightforward but important: oxygenated blood leaves the heart through large arteries, flows into progressively smaller arterioles, and finally reaches the capillary beds where oxygen can diffuse into muscle tissue. Deoxygenated blood then returns through the venous system back to the heart and lungs for re-oxygenation. Training improves this entire delivery system. Over time, endurance exercise increases heart size and stroke volume, expands plasma and red blood cell volume, and improves the heart’s pumping efficiency allowing a higher volume of oxygen-rich blood to be delivered each minute to working organs and active muscle tissues.

The Extraction Side: Capillaries, Mitochondria, and the “Oxygen Sink”

Blood flow is only half the equation. VO₂max also depends on how efficiently tissues can extract oxygen from the blood and use it for energy production. This is captured by the a-vO₂ difference, which reflects how much oxygen is removed from the blood as it passes through working muscles. The greater the difference between arterial oxygen content and venous oxygen content, the more oxygen has been extracted, and the higher the aerobic energy output.

Here, the vasculature and mitochondria converge. Training increases capillary density, improving oxygen diffusion by shortening the distance between blood and muscle fibers. Simultaneously, endurance exercise increases mitochondrial number, size, and enzymatic efficiency, creating a larger and more capable “oxygen sink” inside muscle cells. More capillaries increase oxygen access; more mitochondria increase oxygen utilization. Together, these adaptations raise the ceiling of sustained energy production and form a core biological foundation for endurance, metabolic health, and resilience with aging [12].

Local, Muscle-Specific Remodeling

Importantly, many of these adaptations occur locally, in the tissues most consistently trained or stressed. If an individual cycles nearly every day for six months, the lower body musculature undergoes profound mitochondrial expansion and capillary remodeling, while relatively less trained upper-body muscles show far fewer changes. This localized remodeling explains why exercise modality and muscle recruitment patterns strongly shape physiological outcomes. Most forms of training do not upgrade the muscles throughout the body uniformly. The ones that respond best are consistently exposed to exercise stress.

Muscle Fibers: The Biological Spectrum That Training Reshapes

This local remodeling also reflects the underlying architecture of skeletal muscle, which is composed of fiber types spanning a continuum of metabolic and contractile properties. These fibers differ in mitochondrial density, capillary supply, fuel preference, force output, and fatigue resistance [13–16].

- Type I (slow-twitch) fibers are built for endurance: they contain abundant mitochondria, high capillary density, and rely heavily on aerobic metabolism. They generate lower peak force but resist fatigue extremely well.

- Type IIx (fast-twitch) fibers sit at the opposite end: they contain fewer mitochondria and capillaries, rely more on anaerobic metabolism, and produce high peak force and power—but fatigue quickly.

- Type IIa fibers occupy the middle ground, with mixed metabolic and contractile traits.

This continuum can be visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Muscle fiber-type continuum. Type I fibers have the most mitochondria, capillaries, and oxidative capacity, while type IIx fibers are represented by the other end of the continuum. Type IIa are less specialized and have mixed characteristics shared between Type I and Type IIx.

Training modalities and time domains can alter this spectrum. Endurance training pushes muscle biology toward a more aerobic (oxidative) profile enhancing mitochondrial and vascular networks and improving fatigue resistance, especially within Type I and Type IIa fibers [14]. High intensity exercise and resistance training, in contrast, primarily increases fiber size and force-generating capacity, with comparatively smaller improvements in mitochondrial density and capillary remodeling [17]. In simple terms, the body adapts to the stress it experiences: aerobic training expands the machinery of oxygen use, while anaerobic forms of training expand the skeletal muscle machinery of force production.

For athletes, this creates a familiar tradeoff: maximizing one end of the spectrum can blunt the other. But for individuals focused on longevity, the goal is different. The objective is not peak near-term performance, but durable physiological capacity training in a way that preserves vascular function, mitochondrial health, and force production over decades. That often means diversifying training rather than specializing, building an aerobic foundation while maintaining muscle strength and power are essential safeguards against aging-related decline.

But for individuals focused on longevity, the goal is different. The objective is not peak near-term performance, but durable physiological capacity training in a way that preserves vascular function, mitochondrial health, and force production over decades.

Exercise-Induced Mitochondrial Fission and Mitophagy: How Training Upgrades the Cellular Power Grid

If VO₂max reflects how efficiently oxygen can be delivered and extracted, mitochondria determine what happens next, whether that oxygen is converted into usable cellular energy. Mitochondria are potential bottlenecks that limit endurance, metabolic health, and resilience with aging. One of the most well-documented adaptations to endurance training is an increase in mitochondrial number and density within muscle, a process known as mitochondrial biogenesis [18].

Yet mitochondrial adaptation is more complex than simply making more mitochondria. The deeper story is that exercise forces mitochondria to behave like a dynamic energy network, constantly reshaping itself to meet energy demands with precision. This remodeling includes two tightly linked processes: mitochondrial fission, in which mitochondria split into smaller units, and mitophagy, in which damaged mitochondria are selectively removed and recycled. Together, these processes help explain why exercise improves not only energy production capacity but mitochondrial quality, an increasingly important concept in aging biology.

Studying these changes directly in humans is challenging. Mitochondria remodel rapidly and continuously, meaning much of what we know comes from biological snapshots at specific time points, often requiring invasive muscle biopsies [19]. Capturing fission events in particular is difficult because splitting can occur during exercise itself, and repeated biopsies are essentially minor surgical procedures.

Acute Adaptation: Fission as a Real-Time Response to Energy Stress

A single bout of exercise rapidly activates mitochondrial fission signaling through phosphorylation of Dynamin-Related Protein 1 (DRP1), a key molecular trigger for mitochondrial “splitting” [20]. This response is not a sign of damage; it is a functional adaptation to metabolic stress. In fact, disrupting fission impairs exercise performance, reinforcing that this rapid remodeling is necessary for muscle to meet high energetic demand [20].

A useful way to think about this is that mitochondria are not static power plants; they behave more like a flexible power grid. During exercise, energy demand rises sharply and oxygen and fuel availability fluctuate moment-to-moment. Splitting mitochondria allows the cell to redistribute energy production more efficiently, respond faster to changes in demand, and isolate stressed or damaged organelle components for repair. In the short term, this improves performance; and in the longer term, it sets the stage for deeper structural remodeling.

During exercise, energy demand rises sharply and oxygen and fuel availability fluctuate moment-to-moment. Splitting mitochondria allows the cell to redistribute energy production more efficiently, respond faster to changes in demand, and isolate stressed or damaged organelle components for repair.

Chronic Adaptation: Building and Cleaning the Mitochondrial Network

With repeated training, mitochondrial remodeling shifts from acute fission toward long-term upgrading of the entire network. This chronic adaptation is largely governed by changes in mitochondrial protein turnover and gene expression, orchestrated by PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α), the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis [21].

PGC-1α is often described as the switch that turns on mitochondrial growth programs. Exercise activates PGC-1α, which increases the transcription of genes involved in mitochondrial formation, oxidative metabolism, and energy production. But emerging evidence suggests its role is even more important: PGC-1α appears to coordinate not only the creation of new mitochondria, but also the selective removal of damaged ones through mitophagy, effectively improving both the quantity and quality of the mitochondrial pool.

This dual function is supported by animal models. Deletion of PGC-1α reduces mitochondrial content, impairs endurance performance, and blunts both biogenesis and mitophagy signaling after exercise [21–23]. In other words, without PGC-1α, muscle loses its ability to both build and recycle mitochondria, limiting adaptation and accelerating dysfunction that often accompanies aging.

Exercise as Mitochondrial Quality Control for Aging

The long-term outcome of these processes is not just more mitochondria, but better mitochondria, a more efficient, resilient network that supports improved glucose control, fat oxidation, and metabolic flexibility. Over time, regular training shifts mitochondrial function toward higher efficiency and stronger stress tolerance, helping protect against the mitochondrial decline that accompanies aging and inactivity.

From a healthspan perspective, this is one of exercise’s most powerful benefits. Training does not simply increase energy production during workouts; it improves the body’s ability to generate and regulate energy across everyday life. In practical terms, exercise builds a mitochondrial system with a great reserve capacity, harder to exhaust, easier to recover, and better able to resist the metabolic fragility that often precedes chronic disease and functional decline.

Angiogenesis: Building the Oxygen Delivery Network

If mitochondria are the cellular engines that convert oxygen into usable energy, then capillaries are the delivery routes that determine how much oxygen and fuel actually reaches those engines. Capillaries are the primary site of gas exchange between blood and working tissues, allowing oxygen to diffuse out of the bloodstream and into muscle, while metabolic waste products such as carbon dioxide diffuse back into circulation for removal. In many ways, capillaries represent the “last mile” of the oxygen delivery system and often the most important limiting step for sustained aerobic performance and metabolic resilience.

This is why increases in capillary number and density are so advantageous. More capillaries deliver a greater volume of blood to active tissue, expand the surface area available for diffusion, and shorten the distance oxygen must travel to reach muscle fibers. These changes enhance the arterial–venous oxygen difference (a-vO₂ diff), allowing working tissues to extract more oxygen from the same volume of blood flow [24,25]. In practical terms, capillary remodeling helps the body do more with what it already has, improving efficiency, endurance capacity, and metabolic stability.

The formation of new capillaries and small blood vessels is known as angiogenesis, and it is regulated primarily by vascular growth factors, most notably vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [24]. VEGF acts as a molecular signal that tells the body, this tissue needs more blood supply. It initiates structural remodeling that expands the vascular network in response to repeated energetic demand.

Exercise provides exactly the kind of signal that triggers this remodeling. As cardiac output rises during training, blood flow increases and vessel walls experience greater mechanical shear stress. At the same time, local metabolic changes within muscle such as shifts in oxygen, lactate, and inflammatory signaling create a biochemical environment that reinforces the need for vascular expansion or sprouting new blood vessels [24]. Together, these exercise-induced signals can increase VEGF levels by roughly 1.5–2-fold in circulation, while VEGF expression within skeletal muscle can rise to well over 5-fold [24]. Over time, repeated exposure to these signals drives increases in capillary density and vascular branching within trained muscle.

Importantly, the body does not remodel delivery and utilization systems independently. PGC-1α, best known as the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, also promotes VEGF expression linking angiogenesis and mitochondrial adaptation so that oxygen delivery and oxygen utilization scale together [26,27]. This coordinated remodeling helps explain why endurance-trained individuals consistently exhibit a higher capillary density: the vascular network expands in parallel with mitochondrial capacity, ensuring that the muscle’s increased demand for oxygen can actually be met.

This vascular remodeling becomes even more consequential with age. Aging is associated with progressive declines in cardiovascular function, driven in part by increased arterial stiffness, vascular remodeling, endothelial dysfunction, and a gradual loss of capillaries changes that impair oxygen delivery and diffusion capacity. In this context, exercise-induced angiogenesis is not merely performance-enhancing; it is foundational to preserving tissue oxygenation, metabolic health, and physiological resilience across the lifespan. By maintaining the vascular network that supplies muscle and organ tissue, training helps preserve the biological infrastructure that supports both physical independence and long-term vitality.

Comparing Training Approaches for Inducing Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Angiogenesis

A useful way to think about exercise is that it pushes muscle fibers along a spectrum. At one end, prolonged inactivity nudges muscle toward a phenotype with fewer mitochondria, fewer capillaries, and a greater proportion of Type IIx fibers that produce huge force, but fatigue quickly. Sedentary behavior, and especially extreme inactivity such as bed rest, denervation, or spinal cord injury, accelerates this shift toward Type IIx dominance [28]. The result is a measurable decline in dexterity, fine motor control, oxidative capacity, fatigue resistance, and metabolic flexibility.

Exercise reverses this trajectory but not all exercise does so in the same way. Different training modalities apply different stress signals to muscle and blood vessels, producing distinct patterns of mitochondrial remodeling and angiogenesis. Importantly, training does more than preserve function. In many cases it can build mitochondrial and vascular capacity beyond what is observed even in healthy but sedentary individuals.

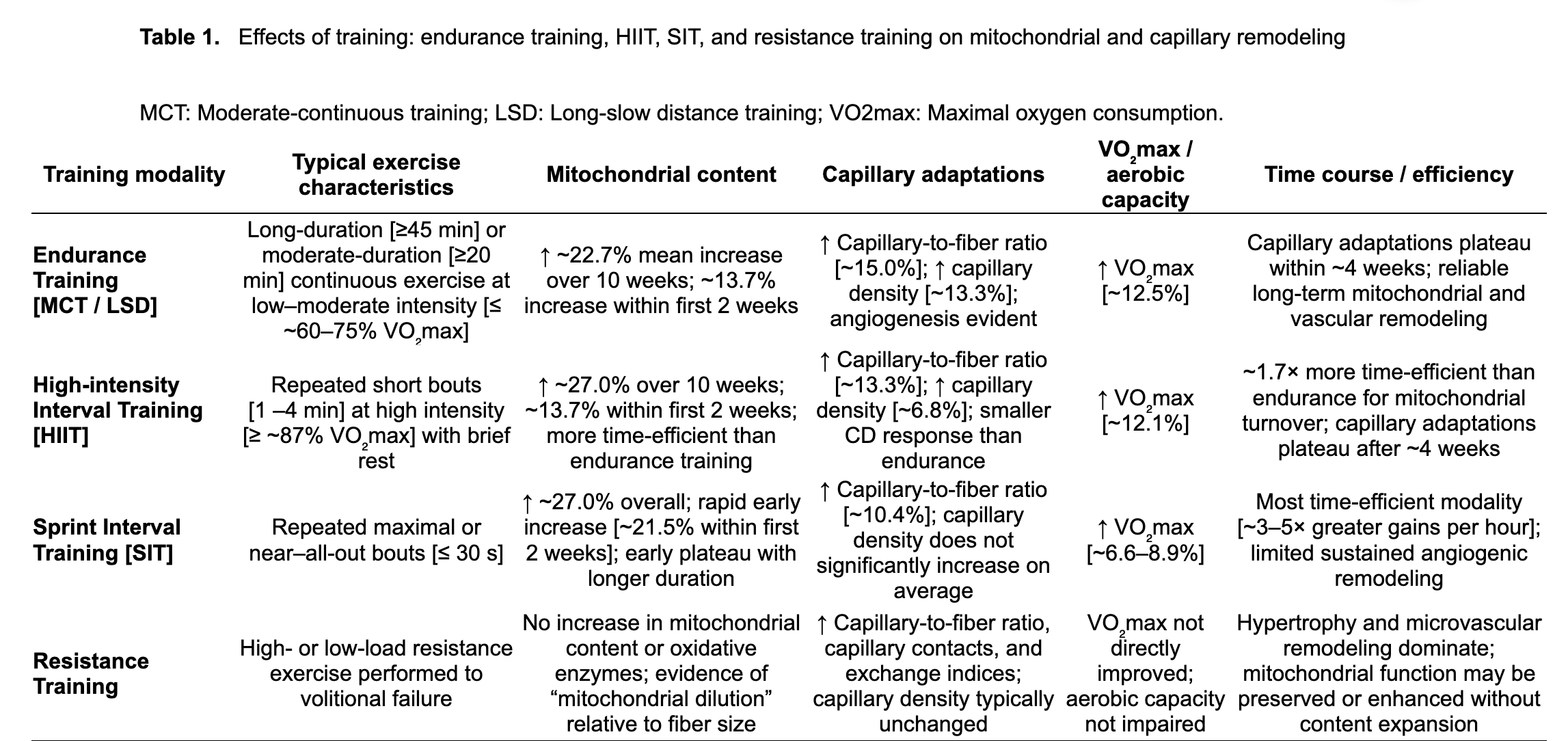

A comprehensive review and meta-regression by Molmen and colleagues, published in 2024, compared the effects of multiple training approaches on mitochondrial content, capillary remodeling, and VO₂max [29]. The findings provide a valuable framework for answering a practical question: If your goal is to improve mitochondrial function and vascular delivery, what kind of training (Endurance, High-Intensity, Sprint) gives you the best return on effort?

Endurance Training: The Most Reliable Builder of Capillary Networks

Traditional endurance training often described as moderate continuous training (MCT) or long slow distance (LSD), or more recently referred to as Zone 2, consists of longer sessions performed at relatively low to moderate intensity. In practice, this often means 60+ minutes at ≤60–65% of VO₂max [29,30].

Example:

- 45 minutes of brisk cycling at a pace you can sustain while still speaking in full sentences

- 30–60 minutes of steady incline walking

- 40 minutes of continuous rowing at moderate effort

Endurance training is the most consistent vascular builder. Because it sustains blood flow for long periods, it repeatedly exposes vessel walls to shear stress and maintains elevated oxygen demand long enough to trigger angiogenic signaling. It also produces strong mitochondrial adaptations because muscles must repeatedly rely on oxidative metabolism for prolonged work.

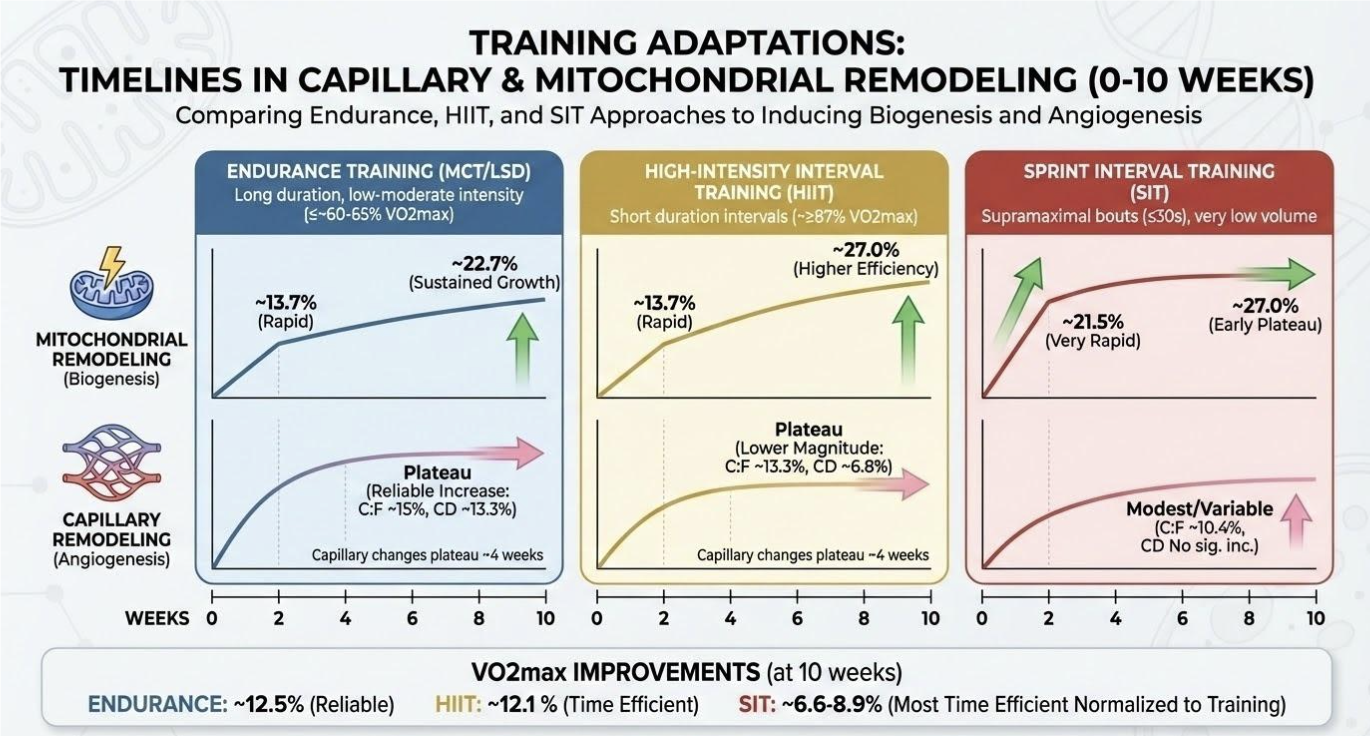

Across studies synthesized by Molmen et al., endurance training produced:

- ~22.7% increase in mitochondrial content over 8–10 weeks

- ~15.0% increase in capillary-to-fiber ratio

- ~13.3% increase in capillary density

- ~12.5% increase in VO₂max

A key insight is that adaptations occur early. A substantial portion of mitochondrial change occurs within the first two weeks (~13.7%) [29]. Capillary remodeling also appears to reach a plateau after ~4 weeks [29], suggesting that the “easy wins” of angiogenesis occur early, and additional vascular gains may require either higher training volume, progression, or varied intensity. Endurance training is the most reliable modality for improving both mitochondrial biogenesis and angiogenesis, especially capillary density.

HIIT: Time-Efficient Mitochondrial Remodeling with Strong VO₂max Gains

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) applies a different stimulus: repeated shorter bouts of near-maximal aerobic effort (≥87% VO₂max) separated by recovery periods [29]. These intervals create a strong metabolic contrast, high oxygen demand, high lactate, high energy turnover that rapidly activates mitochondrial signaling.

Example:

- 4 × 4 minutes hard (breathing heavy), with 3 minutes easy recovery

- 10 × 1 minute hard / 1 minute easy

- 6 × 2 minutes hard / 2 minutes easy

HIIT became popular because it compresses a strong stimulus into less time. In the Molmen synthesis, HIIT produced:

- ~27.0% increase in mitochondrial content over 10 weeks

- ~13.3% increase in capillary-to-fiber ratio

- ~6.8% increase in capillary density

- ~12.1% increase in VO₂max

Compared with endurance training, HIIT was estimated to be ~1.7× more time-efficient for driving mitochondrial adaptations [29]. However, capillary density gains were smaller. One plausible explanation is that HIIT tends to increase muscle cross-sectional area more than steady endurance training, which can make capillary density (capillaries per mm²) appear less improved even if total capillaries increase.

As with endurance training, angiogenic gains plateau around 4 weeks [29], suggesting early vascular remodeling occurs rapidly and then stabilizes. HIIT is a powerful tool for improving VO₂max and mitochondrial capacity quickly, with moderate angiogenic benefits, especially useful when time is limited.

Sprint Interval Training (SIT): The Fastest Mitochondrial Signal per Minute

Sprint interval training (SIT) takes intensity one step further. SIT consists of repeated supramaximal or true peak “all-out” efforts (usually lasting ≤30 seconds) with longer recovery, often at least 2-4 times the duration of exercise. Total training volume is extremely low, but the physiological signals include rapid ATP depletion, high lactate accumulation, and strong mitochondrial adaptations relative to the time domain of exercise.

Example:

- 4–6 × 20–30 second all-out sprints on a bike, with 2–4 minutes recovery

- 6 × 10–15 second hill sprints, long walk-down recovery

Despite its brevity, SIT robustly stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and improves aerobic capacity [29,34,35]. In Molmen et al., SIT produced:

- ~27.0% increase in mitochondrial content

- ~21.5% of adaptation occurring in the first two weeks

- ~10.4% increase in capillary-to-fiber ratio

- no significant average increase in capillary density

- ~6.6–8.9% increase in VO₂max

SIT’s “superpower” is time efficiency. When normalized to total training time, SIT generated ~3–5× greater VO₂max gains per hour of exercise than other modalities [29]. The tradeoff is vascular remodeling; SIT is less effective than endurance training at building sustained angiogenesis, and mitochondrial improvements appear to plateau early rather than steadily rising with longer interventions. SIT is the most time-efficient stimulus for rapid mitochondrial gains, but it is not the best standalone strategy for long-term capillary expansion.

What About Resistance Training?

Resistance exercise belongs in its own category because it targets a different biological problem. Endurance and interval training primarily expand oxygen delivery and utilization. Resistance training primarily expands force production capacity, preserving muscle mass, strength, and structural integrity traits strongly tied to independence and survival in aging.

Mechanistically, resistance training produces hypertrophy and microvascular remodeling, but typically not robust mitochondrial biogenesis in young, healthy individuals [36]. Studies show that resistance training performed to volitional failure increases Type I and Type II fiber cross-sectional area, alongside improvements in: capillary-to-fiber ratio, capillary contacts, capillary exchange indices, while capillary density often remains unchanged [36–38].

This pattern suggests that angiogenesis occurs largely in proportion to fiber growth, helping preserve diffusion capacity as muscle expands rather than through absolute expansion of capillary networks as seen in endurance training.

Mitochondrial adaptation is also distinct. Resistance training often produces a phenomenon described as mitochondrial dilution as muscle fibers grow faster than the number increases, resulting in a lower mitochondrial density within a given muscle, even if function is preserved [36–38]. Importantly, this does not necessarily imply worse mitochondrial performance. Several studies report preserved or even improved mitochondrial respiratory efficiency and electron transport chain activity after resistance training [36–38]. Additionally, age and baseline fitness matter as older or less active individuals often show more consistent mitochondrial functional improvements from resistance training [36–38]. Resistance training is essential for healthspan because it preserves strength and muscle mass, while supporting microvascular supply. But it produces a different mitochondrial signature than aerobic training and should be viewed as complementary rather than a replacement alternative.

Putting It All Together: Choosing the Right Tool for the Job

From a longevity perspective, these training modalities should not be framed as competitors. They are different tools that stress different biological systems:

- Endurance training = best for building capillary networks and aerobic foundation

- HIIT = best for time-efficient VO₂max + mitochondrial remodeling

- SIT = best for rapid mitochondrial signaling per minute trained

- Resistance training = best for strength, muscle preservation, and aging resilience

For healthspan, the optimal strategy is rarely specialization. Instead, the strongest approach is training diversity: combining endurance and intervals to support vascular–mitochondrial infrastructure while using resistance training to preserve muscle mass, power, and independence.

A summary of all modalities and their relative effects on mitochondrial and capillary adaptations is shown in Table 1.

Time Efficiency and the Minimum Effective Dose

The physiology reviewed above makes one point clear: different training styles upgrade the mitochondria and vascular system through different routes. But in real life, the limiting factor is rarely biology; it is feasibility. Time constraints, injury risk, motivation, and day-to-day energy all shape whether someone can train consistently for years rather than weeks. From a healthspan perspective, this raises a practical question that matters as much as any mechanistic detail:

What is the minimum amount of training needed to meaningfully improve mitochondrial and vascular health, and which modality delivers the greatest return on time invested?

This is where the concept of time efficiency becomes essential. The “best” training program is not the one that produces the largest physiological change in a lab; it is the one a person can actually sustain across the lifespan. The Molmen et al. meta-analysis provides useful guidance by comparing how quickly different modalities drive mitochondrial and vascular remodeling [29].

Sprint Interval Training (SIT): Mitochondrial Gains in Minimal Time

Sprint interval training (SIT) appears to be the most time-efficient tool for stimulating mitochondrial adaptation. Despite very low total training volume, SIT produces large and rapid increases in mitochondrial content, with a substantial share of the total adaptation occurring within the first two weeks of training [29]. When expressed relative to time invested, SIT generates several-fold greater gains per hour of exercise compared with endurance and interval training [29].

A helpful way to interpret this is that mitochondrial biogenesis is highly sensitive to brief, intense metabolic disruption, especially when the body is not yet adapted. SIT delivers that disruption efficiently. From a healthspan perspective, SIT may be most useful during periods when time, motivation, or exercise capacity is limited. It can quickly activate mitochondrial signaling pathways and rebuild aerobic capacity with minimal time commitment, but the peak intensity requires that you consider risks and potential physical limitations.

However, SIT also has limitations. The rapid plateau observed with longer SIT interventions suggests it may be better suited for initiating adaptation rather than sustaining progressive remodeling over months and years [29]. And because SIT requires repeated near-maximal efforts, it can carry higher barriers in terms of discomfort, orthopedic strain, and adherence.

SIT is the most time-efficient mitochondrial stimulus, and represents a valuable strategy to maintaining or building mitochondrial health.

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT): Efficient Balanced Benefits

HIIT offers a more balanced strategy, less extreme than SIT, but far more time-efficient than traditional endurance training. In the Molmen synthesis, HIIT produced mitochondrial gains comparable to endurance training over similar durations, while requiring substantially less total exercise time [29].

Crucially, HIIT appears to support continued aerobic and mitochondrial improvements over longer training periods, unlike SIT, which tends to plateau earlier [29]. This makes HIIT particularly relevant for healthspan. HIIT can be intense enough to drive meaningful adaptation, while still being tolerable enough to sustain across months or years. HIIT is often the most realistic high-yield option for people who want strong mitochondrial and VO₂max gains without peak intensity demands.

Endurance Training: The Gold Standard Long-term Strategy

Although less time-efficient, endurance training remains the gold standard for building a durable aerobic foundation. It reliably improves VO₂max and mitochondrial content, but it also produces the strongest and most consistent improvements in capillary density, a key determinant of oxygen delivery, substrate exchange, and fatigue resistance [29].

This matters because vascular decline is a major feature of aging: capillary loss, endothelial dysfunction, and reduced tissue perfusion all contribute to reduced exercise tolerance and metabolic fragility. Endurance training directly counteracts these trends by reinforcing the vascular network that supports long-term tissue health.

While endurance adaptations appear early and may plateau within weeks, their sustained presence may be essential for preserving metabolic stability and exercise tolerance across the lifespan [29]. Endurance training may not win on time efficiency, but it remains uniquely valuable for long-term vascular health and the durability of aerobic adaptations.

Putting Minimum Effective Dose Into Context

Taken together, these findings suggest that a small amount of high-intensity work can trigger large mitochondrial benefits, while longer, steadier training remains uniquely valuable for vascular remodeling. For healthspan programming, the most effective approach is often not choosing one modality; rather, combining them is the best strategy.

Meaningful mitochondrial and vascular benefits do not require marathon training. What matters most is applying the right stimulus at a dose that is sustainable and repeating it consistently enough for biology to compound over time. Mitochondrial and vascular adaptations occur on different timelines. Figure 2 below summarizes the typical time course of mitochondrial remodeling and capillary expansion in response to training.

Figure 2. Time course of vascular and mitochondrial adaptations to various training approaches as described in the meta-regression from Molmen et al., 2024. C:F: Capillary to muscle fiber ratio; CD: Capillary density.

Practical Translation for Older Adults and Time-Constrained Individuals

One of the central challenges in translating exercise science into healthspan strategy is not whether exercise works, it is whether people can do it consistently for decades. Aging trajectories vary widely, and the practical constraints of real life often become more limiting than physiology itself. Time scarcity, orthopedic limitations, declining recovery capacity, and reduced exercise tolerance can all shape what training is feasible, particularly in older adults [39,40]. For these populations, the goal is not to chase a single “best” modality. It is to build a program that is adaptable, biologically effective, and sustainable.

This is where the emerging evidence becomes encouraging. Collectively, the data challenge the assumption that large exercise volumes are required to produce meaningful mitochondrial and vascular adaptations. Mitochondrial content and oxidative capacity can respond rapidly especially when intensity is used strategically while capillary remodeling often occurs early and does not scale linearly with ever-increasing training volume. In other words, more training is not always proportionally better. For many individuals, especially those with limited time or limited tolerance, the most important step is identifying the minimum stimulus that reliably produces adaptation, then repeating it consistently enough for those benefits to accumulate.

A practical implication follows: intensity can often substitute for time, but only when applied thoughtfully. Higher-intensity interval approaches may deliver greater physiological return per unit time, making them appealing for time-constrained individuals. Yet the same intensity that makes interval training efficient can also increase injury risk, discomfort, and recovery demands especially in older adults. The optimal strategy is therefore not maximal intensity, but appropriate intensity: enough to activate mitochondrial and cardiovascular remodeling, without exceeding the individual’s orthopedic or recovery limits.

Rather than viewing endurance, interval, sprint, and resistance training as competing approaches, the evidence supports a complementary framework in which each modality contributes distinct benefits. High-intensity approaches such as sprint interval training can rapidly stimulate mitochondrial adaptation, but often plateau early. Endurance and HIIT provide more gradual, sustainable remodeling particularly of the microvasculature supporting oxygen delivery and long-term aerobic durability. Resistance training, while not a primary driver of mitochondrial biogenesis, remains essential for preserving muscle mass, strength, and functional independence, while maintaining capillary supply in proportion to muscle fiber size.

In practice, this opens the door to a flexible “sequencing” approach that fits real life. Short blocks of higher-intensity training can be used to rapidly re-engage mitochondrial adaptation particularly after sedentary periods followed by more moderate endurance or interval training to consolidate vascular benefits and sustain aerobic capacity. For example, a time-limited individual might use brief interval sessions during a busy month, then shift toward longer steady training when schedule and recovery allow. Similarly, an older adult might prioritize low-impact intervals (cycling, incline walking, rowing) that provide cardiovascular stimulus without excessive joint stress, while maintaining resistance training as the anchor for strength and mobility.

Ultimately, the most important determinant of long-term benefit is not the perfect modality, it is consistency. But variation can help sustain consistency. Rotating training styles across weeks or seasons allows individuals to tap different adaptive pathways, avoid plateaus, reduce overuse injury risk, and maintain engagement. This is especially relevant for healthspan, where the goal is not a short-term performance peak, but preserving mitochondrial and vascular function and the quality of life they support across the lifespan.

In the next section, we translate these principles into practical minimum effective dose templates, offering realistic weekly structures that prioritize mitochondrial and vascular health under different time and capacity constraints.

Minimum Effective Dose (MED) Training Templates for Mitochondrial + Vascular Health

One of the most encouraging findings in modern exercise physiology is that meaningful mitochondrial and vascular benefits do not require extreme training volumes. The body responds strongly to relatively small doses especially when intensity is used strategically. Below are evidence-informed weekly templates that balance time efficiency with long-term sustainability.

Important note: These are not rigid prescriptions. They are practical starting points that can be adjusted based on age, injury history, baseline fitness, and recovery capacity.

The Busy Week Minimum (≈30 minutes/week)

Goal: Preserve mitochondrial signaling and aerobic capacity when time is limited

Best for: High workload schedules, travel, or “maintenance mode”

Option A (HIIT-based):

- 2 sessions/week

- 10–15 minutes each

- Example: 6 × 1 minute hard / 1 minute easy, plus warm-up/cool-down

Option B (SIT micro-dose):

- 1 session/week

- 10–15 minutes total

- Example: 4–6 × 20–30 second sprints with long recovery

A small number of intense bouts can reactivate mitochondrial biogenesis signaling and preserve VO₂max surprisingly well, especially in previously trained individuals. Think of this as the minimum dose to keep the system online.

The High-Return Healthspan Dose (≈60–90 minutes/week)

Goal: Improve VO₂max, mitochondrial content, and maintain vascular remodeling

Best for: Most people pursuing healthspan; excellent benefit-to-time ratio

Example weekly structure:

1 HIIT session (15–25 min)

- Example: 4 × 4 minutes hard / 3 minutes easy

1 endurance session (30–45 min)

- Zone 2 pace: sustainable, conversational intensity

- Optional: 1 short easy session (10–20 min walk/bike)

This is the “sweet spot” where you get robust mitochondrial adaptation and enough steady blood-flow time to support capillary remodeling and vascular health.

The Long-term Longevity Builder (≈2.5–3 hours/week)

Goal: Maximize mitochondrial capacity + build long-term vascular durability

Best for: Individuals prioritizing long-term aerobic performance, metabolic resilience, and maximal physiological reserve

Example weekly structure:

- 2 endurance sessions (40–60 min each)

- 1 HIIT session (20–30 min total work)

- 1 optional easy recovery session (20–30 min)

This time and effort investment tends to produce the most reliable long-term improvements in capillary density, mitochondrial remodeling, metabolic flexibility, and aerobic durability. It builds a deeper, more diverse, fitness reserve, which becomes increasingly valuable with aging.

Where Resistance Training Fits

For healthspan, aerobic work is only half the equation. To preserve independence and reduce frailty risk, resistance training should be layered in:

Minimum effective resistance dose:

- 2 sessions/week (30–60 minutes)

- Focus on major movement patterns: squat/hinge/push/pull/carry

Why it matters: Resistance training preserves muscle mass, strength, and power, while supporting microvascular remodeling, complementing the mitochondrial and angiogenic benefits of aerobic training.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Exercise is one of the most powerful healthspan interventions because it strengthens two systems that decline with age: vascular delivery and mitochondrial energy production. Across modalities, the evidence shows that meaningful improvements in both can be achieved often with surprisingly modest doses so long as training is applied consistently and matched to individual capacity. The practical takeaway is not that one style is superior, but that each serves a distinct role: endurance training supports vascular durability and capillary remodeling, HIIT and sprint work provide time-efficient mitochondrial and VO₂max gains, and resistance training preserves muscle mass and functional independence as aging progresses.

Key questions remain about long-term application, including how to disentangle intensity from volume in time-matched studies and why some adaptations plateau, particularly angiogenesis. Future trials designed around equal time commitments and longer follow-up will help refine minimum effective doses and personalize training prescriptions. Ultimately, longevity-focused exercise is less about maximizing performance and more about sustaining physiological reserve, building an energy and delivery infrastructure that supports independence, metabolic health, and vitality across the lifespan.

- Stewart, K. J., Bacher, A. C., Turner, K., Lim, J. G., Hees, P. S., Shapiro, E. P., Tayback, M., & Ouyang, P. (2005). Exercise and risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome in older adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(1), 9‑18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.006

- Spanoudaki M, Giaginis C, Karafyllaki D, Papadopoulos K, Solovos E, Antasouras G, Sfikas G, Papadopoulos AN, Papadopoulou SK. Exercise as a Promising Agent against Cancer: Evaluating Its Anti-Cancer Molecular Mechanisms. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Oct 25;15(21):5135. doi: 10.3390/cancers15215135. PMID: 37958310; PMCID: PMC10648074.

- Kraus, W. E., Powell, K. E., Haskell, W. L., Janz, K. F., Campbell, W. W., Jakicic, J. M., Troiano, R. P., Sprow, K., Torres, A., & Piercy, K. L. (2019). Physical activity, all‑cause and cardiovascular mortality, and cardiovascular disease. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 51(6), 1270‑1281. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001939

- Tomás, M. T., Galán‑Mercant, A., Alvarez Carnero, E., & Fernandes, B. (2017). Functional capacity and levels of physical activity in aging: A 3‑year follow‑up. Frontiers in Medicine, 4, 244. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2017.00244

- Brogno, B. (2025). Aging with strength: Functional training to support independence and quality of life. Inquiry, 62, 00469580251348133. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580251348133

- Hyvärinen, M., Kankaanpää, A., Rantalainen, T., Rantanen, T., Laakkonen, E. K., & Karavirta, L. (2025). Body composition and functional capacity as determinants of physical activity in middle‑aged and older adults: A cross‑sectional analysis. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, 22, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556‑025‑00372‑z

- Satsangi, M., & Tadi, P. (2023). Physiology, vascular. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Bookshelf

- Cooper, G. M., & Hausman, R. E. (2000). Mitochondria. In The Cell: A Molecular Approach (2nd ed.). Sinauer Associates. (NCBI Bookshelf entry

- Ungvari, Z., Sonntag, W. E., & Csiszar, A. (2010). Mitochondria and aging in the vascular system. Journal of Molecular Medicine, 88(10), 1021‑1027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109‑010‑0667‑5

- Wang, S., Pi, Y., Yang, X., et al. (2023). New insights into vascular aging: Emerging role of mitochondria function. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 162, Article 114592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114592

- Jani, B., & Rajkumar, C. (2006). Ageing and vascular ageing. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 82(968), 357‑362. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2005.036053

- Strasser, B., & Burtscher, M. (2018). Survival of the fittest: VO₂max, a key predictor of longevity? Frontiers in Bioscience (Landmark Edition), 23, 1505‑1516. https://doi.org/10.2741/4657

- Pette, D., & Staron, R. S. (2000). Myosin isoforms, muscle fiber types, and transitions. Microscopy Research and Technique, 50(6), 500‑509. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097‑0029(20000915)50:6

- Plotkin, D. L., Roberts, M. D., Haun, C. T., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2021). Muscle fiber type transitions with exercise training: Shifting perspectives. Sports (Basel), 9(9), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports9090127

- Poole, D. C., Copp, S. W., Ferguson, S. K., & Musch, T. I. (2012). Anatomy of skeletal muscle and its vascular supply. In Skeletal Muscle Circulation (Chapter 2). Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences

- Ørtenblad, N., Nielsen, J., Boushel, R., Saltin, B., & Holmberg, H.‑C. (2018). The muscle fiber profiles, mitochondrial content, and enzyme activities of the exceptionally well‑trained arm and leg muscles of elite cross‑country skiers. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 1031. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01031

- Hickson, R. C., Hidaka, K., & Foster, C. (1994). Skeletal muscle fiber type, resistance training, and strength‑related performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 26(5), 593‑598

- Memme, J. M., Erlich, A. T., Phukan, G., & Hood, D. A. (2021). Exercise and mitochondrial health. The Journal of Physiology, 599(3), 803‑817. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP278853

- Musci, R. V., Hamilton, K. L., & Linden, M. A. (2019). Exercise‑induced mitohormesis for the maintenance of skeletal muscle and healthspan extension. Sports, 7(7), Article 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7070170

- Moore, T. M., et al. (2019). The impact of exercise on mitochondrial dynamics and the role of Drp1 in exercise performance and training adaptations in skeletal muscle. Molecular Metabolism, 21, 51‑67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2018.11.012

- Halling, J. F., & Pilegaard, H. (2020). PGC‑1α‑mediated regulation of mitochondrial function and physiological implications. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 45(9), 927‑936. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm‑2020‑0005

- Geng, T., Li, P., Okutsu, M., Yin, X., Kwek, J. Y., Zhang, M., & Yan, Z. (2010). PGC‑1α plays a functional role in exercise‑induced mitochondrial biogenesis and angiogenesis but not fiber‑type transformation in mouse skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology – Cell Physiology, 298(3), C??–C?? (issue pages). https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00481.2009

- Chen, L., Qin, Y., Liu, B., Gao, M., Cai, Y., et al. (2022). PGC‑1α‑mediated mitochondrial quality control: Molecular mechanisms and implications for heart failure. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 10, Article 871357. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.871357

- Ross, M., Kargl, C. K., Ferguson, R. G., Poggi, T. P., & Vila, J. (2023). Exercise‑induced skeletal muscle angiogenesis: Impact of age, sex, angiocrines and cellular mediators. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 123(7), 1415‑1432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421‑022‑05128‑6

- Duscha, B. D., Kraus, W. E., Keteyian, S. J., Sullivan, M. J., Green, H. J., Schachat, F. H., Pippen, A. M., Brawner, C. A., Blank, J. M., & Annex, B. H. (1999). Capillary density of skeletal muscle: A contributing mechanism for exercise intolerance in class II–III chronic heart failure independent of other peripheral alterations. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 33(7), 1956‑1963. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735‑1097(99)00101‑1

- Arany, Z., Foo, S.‑Y., Ma, Y., Ruas, J. L., Bommi‑Reddy, A., Girnun, G., Cooper, M., Laznik, D., Chinsomboon, J., Rangwala, S. M., Baek, K. H., Rosenzweig, A., & Spiegelman, B. M. (2008). HIF‑independent regulation of VEGF and angiogenesis by the transcriptional coactivator PGC‑1α. Nature, 451, 1008‑1012. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06613

- Løck, L., Hellsten, Y., Fentz, J., Lyngby, S. S., Wojtaszewski, J. F. P., Hidalgo, J., & Pilegaard, H. (2009). PGC‑1α mediates exercise‑induced skeletal muscle VEGF expression in mice. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and Metabolism, 297(1), E??–E?? (issue pages). https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00076.2009

- Burnham, R., Martin, T., Stein, R., Bell, G., MacLean, I., & Stewart, C. (1997). Skeletal muscle fibre type transformation following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, 35(2), 86‑91. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3100364

- Mølmen, K. S., Almquist, N. W., & Skattebo, Ø. (2025). Effects of exercise training on mitochondrial and capillary growth in human skeletal muscle: A systematic review and meta‑regression. Sports Medicine, 55(1), 115‑144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279‑024‑02120‑2,

- MacIntosh, B. R., Murias, J. M., Keir, D. A., & Weir, J. M. (2021). What is moderate to vigorous exercise intensity? Frontiers in Physiology, 12, Article 682233. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.682233

- Ingjer, F. (1979). Effects of endurance training on muscle fibre ATP‑ase activity, capillary supply and mitochondrial content in man. The Journal of Physiology, 294, 419‑432. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012938

- Baum, O., Gubeli, J., Friese, S., Tschanz, E., Malik, C., Odriozola, A., Graber, F., & Hoppeler, H. (2015). Angiogenesis‑related ultrastructural changes to capillaries in human skeletal muscle in response to endurance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 119(10), 1119‑1127. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00594.2015

- Milanović, Z., Sporiš, G., & Weston, M. (2015). Effectiveness of high‑intensity interval training (HIT) and continuous endurance training for VO₂max improvements: A systematic review and meta‑analysis of controlled trials. Sports Medicine, 45, 1469‑1481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279‑015‑0365‑0

- Jacobs, R. A., Flück, D., Bonne, T. C., Bürgi, S., Christensen, P. M., & Lundby, C. (2013). Improvements in exercise performance with high‑intensity interval training coincide with an increase in skeletal muscle mitochondrial content and function. Journal of Applied Physiology, 115(6), 785‑793. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00445.2013

- Mitchell, E. A., Martin, N. R. W., Turner, M. C., Taylor, C. W., & Ferguson, R. A. (2018). The combined effect of sprint interval training and post‑exercise blood flow restriction on critical power, capillary growth, and mitochondrial proteins in trained cyclists. Journal of Applied Physiology, 126(1), 79‑90. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01082.2017

- Parry, H. A., Roberts, M. D., & Kavazis, A. N. (2020). Human skeletal muscle mitochondrial adaptations following resistance exercise training. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(6), 349‑359. https://doi.org/10.1055/a‑1121‑7851

- Porter, C., Reidy, P. T., Bhattarai, N., Sidiropoulos, N., & Rasmussen, B. B. (2015). Resistance exercise training alters mitochondrial function in human skeletal muscle. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 47(9), 1922‑1931. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000605

- Holloway, T. N., Morton, R. W., Oikawa, S. Y., McKellar, S., Baker, S. K., & Phillips, S. M. (2018). Microvascular adaptations to resistance training are independent of load in resistance‑trained young men. American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 315(2), R293‑R301. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00118.2018

- Hyvärinen, M., Kankaanpää, A., Rantalainen, T., Rantanen, T., Laakkonen, E. K., & Karavirta, L. (2025). Body composition and functional capacity as determinants of physical activity in middle‑aged and older adults: A cross‑sectional analysis. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, 22, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556‑025‑00372‑z

- Balicki, P., Sołtysik, B. K., Borowiak, E., Kostka, T., & Kostka, J. (2025). Activities of daily living limitations in relation to the presence of pain in community‑dwelling older adults. Scientific Reports, 15, Article 15027. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598‑025‑00241‑w

Related studies