Alpha-Lactalbumin: A High-Tryptophan Whey Fraction With Distinct Benefits for Muscle Recovery, Sleep, Metabolic Health, and Cognitive Performance

Prefer to listen? Hit play for a conversational, audio‑style summary of this article’s key points.

Alpha-lactalbumin is a unique whey fraction naturally rich in tryptophan as well as branched-chain amino acids for muscle recovery, sleep, metabolic, and cognitive health benefits

Alpha-lactalbumin contains enough leucine to activate the leucine trigger and stimulate muscle protein synthesis in much the same way that whey protein does

Its high tryptophan-to-LNAA ratio potentially improves sleep metrics, next-day alertness, and mood regulation.

Alpha-lactalbumin supplementation has been shown to increase plasma tryptophan up to 300%

Presleep ingestion of alpha-lactalbumin may enhance overnight energy expenditure, improve satiety, and body composition.

Neurocognitive benefits and stress resilience effects have been observed through modulation of serotonin and central fatigue pathways.

Introduction: Alpha-Lactalbumin and the Expanding Definition of Protein Quality

For decades, whey protein has been regarded as the gold standard for muscle repair and post-exercise recovery. Its rapid digestion, high essential amino acid content, and ability to stimulate muscle protein synthesis, the biological process by which dietary protein supports the building and repair of muscle tissue, have made it foundational in sports nutrition, aging research, and clinical recovery settings. As a result, protein quality has traditionally been judged largely by its anabolic potential.

However, dietary protein influences far more than skeletal muscle. Protein intake interacts with sleep regulation, circadian timing, metabolic efficiency, immune defense, and brain chemistry. These systems are biologically interconnected, yet nutritional research has often examined them in isolation. This separation has limited understanding of how specific protein sources may support whole-body physiology.

Within this context, researchers have begun to question the assumption that all high-quality whey proteins function identically. Whey is not a single compound, but a mixture of biologically active proteins, each with distinct amino acid profiles and physiological roles. As scientific focus has shifted from total protein intake toward protein composition, timing, and functional specificity, interest has grown in individual whey fractions that may exert broader biological effects.

One such fraction is alpha-lactalbumin.

Alpha-lactalbumin is a whey protein that plays a central biological role in human milk, accounting for a substantial proportion of total protein (22%). Human milk supports not only growth, but also neurodevelopment, immune maturation, metabolic programming, and circadian rhythm formation during early life. Alpha-lactalbumin’s prominence in this context has prompted investigation into whether its amino acid composition may support similar physiological processes later in life. [1].

What distinguishes alpha-lactalbumin from conventional whey protein is the balance of its amino acids. It is rich in essential and branched-chain amino acids, including leucine, a key nutritional signal involved in muscle repair and recovery. At the same time, it contains a comparatively high concentration of tryptophan, an essential amino acid that serves as a precursor for serotonin and melatonin, signaling molecules involved in mood regulation and sleep. How these amino acids interact within the body and whether they can be leveraged simultaneously remain active areas of research.

Early research suggests that alpha-lactalbumin may influence multiple physiological systems, including muscle recovery, sleep regulation, metabolic function, and neurocognitive performance. However, the magnitude, consistency, and context of these effects depend on factors such as dose, timing, energy intake, and individual physiology.

This article examines the current scientific evidence surrounding alpha-lactalbumin, focusing on its amino acid composition, metabolic pathways, and clinical research across muscle, sleep, metabolic, and cognitive domains. Rather than treating protein solely as a building material for muscle, this review explores how targeted protein formulation may influence interconnected biological systems relevant to long-term health and healthspan.

Protein Quality and Composition

Historically, isolating alpha-lactalbumin (α-LAC) in high purity was technically challenging, limiting both its availability and scientific study. Recent advances in protein filtration and fractionation have now made it possible to produce highly purified α-LAC as a standalone protein source. Unlike many dairy-derived protein supplements, α-LAC contains minimal fat and substantially lower lactose levels, reducing common triggers of dairy intolerance. At the same time, it retains the anabolic properties of high-quality whey protein while introducing additional physiological benefits linked to mood, sleep, and metabolic regulation.

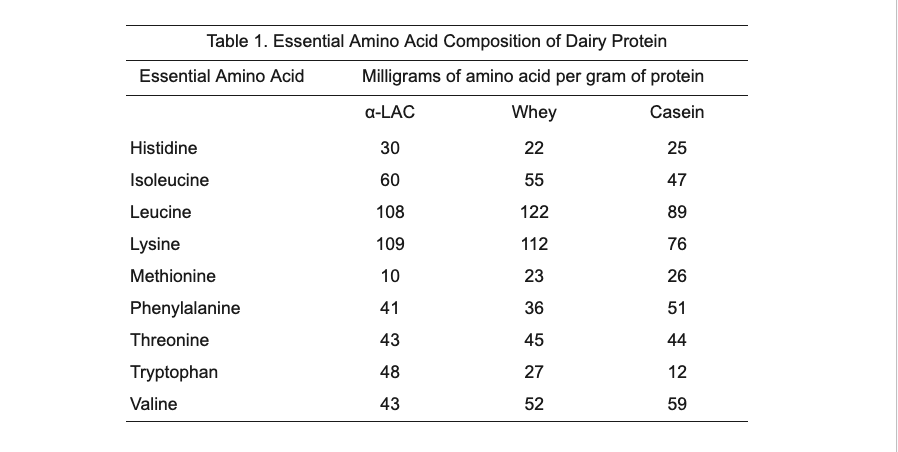

Among isolated dairy proteins, including whey and casein, α-LAC stands out for its distinctive essential amino acid composition. Essential amino acids must be obtained from the diet and play a central role in determining protein quality and biological effectiveness. Alpha-lactalbumin is particularly rich in lysine, cysteine, and the branched-chain amino acids leucine, isoleucine, and valine, while also containing a comparatively high concentration of tryptophan. Notably, the tryptophan content of α-LAC is nearly double that of standard whey protein, at approximately 48 mg per gram compared with 27 mg per gram. This amino acid profile positions α-LAC at the intersection of muscle metabolism and neurochemical regulation. [1]

Branched-chain amino acids, and leucine in particular, play a critical role in muscle protein synthesis by acting as metabolic signals rather than simply structural building blocks. Whey protein has long been considered the reference standard for activating this process and has been extensively studied for its ability to stimulate post-exercise muscle repair and adaptation [2][3]. Both whey protein and α-LAC contain approximately 10 percent leucine by weight, meaning that a 20-gram serving provides roughly 2 grams of leucine. This amount aligns with research identifying a leucine threshold required to maximally stimulate muscle protein synthesis, especially in older adults who experience anabolic resistance and require more precise amino acid signaling to achieve the same anabolic response [4][5][6].

Figure 1. Alpha-Lactalbumin Leucine Trigger Mimics Whey Muscle Protein Synthesis. Adapted from “Fast whey protein and the leucine trigger”, Burd and Philips. 2010, Nutra Foods, Volume 9 (Issue 4), 7-11.

Figure 1 illustrates that α-LAC produces a rapid rise in circulating leucine comparable to whey protein, reaching the leucine threshold associated with maximal muscle protein synthesis. In contrast, slower-digesting or lower-quality protein sources fail to achieve the same peak leucine concentration within the critical postprandial window.

In addition to its branched-chain amino acid content, α-LAC is naturally rich in cysteine, an amino acid central to antioxidant defense and cellular energy metabolism. Cysteine is a required precursor for glutathione synthesis, and its availability often limits glutathione production within cells. Compared with standard whey protein, α-LAC has a higher cysteine-to-methionine ratio greater than one, a feature associated with enhanced antioxidant capacity and immune support [1]. Glutathione plays a central role in neutralizing reactive oxygen species generated during metabolism and physical stress, as well as in detoxification pathways that protect cells from environmental and metabolic toxins [7][8].

Cysteine-derived sulfur also supports mitochondrial energy production through the formation of iron–sulfur clusters, which are essential structural components of several enzymes in the electron transport chain. These enzymes are required for efficient ATP generation, linking α-LAC’s amino acid profile not only to muscle recovery, but also to broader cellular energy efficiency and metabolic resilience [7].

Taken together, the amino acid composition of alpha-lactalbumin distinguishes it from conventional whey protein. It delivers anabolic signaling sufficient to support muscle protein synthesis while simultaneously providing amino acids that support antioxidant defense, mitochondrial function, and neurochemical pathways. This combination allows α-LAC to function as a lower-calorie, highly digestible protein source with physiological effects that extend beyond muscle alone.

Tryptophan Metabolism and Sleep

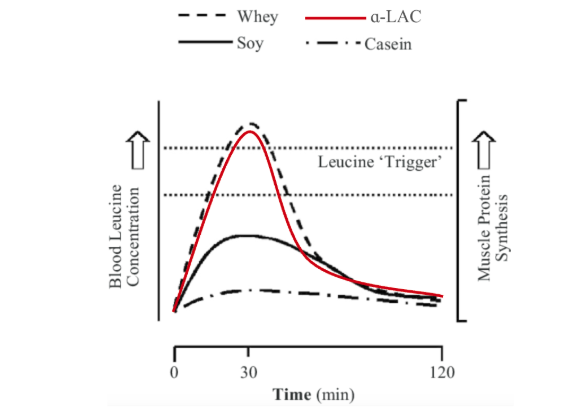

The connection between alpha-lactalbumin and sleep is rooted in its unusually high relative concentration of the essential amino acid tryptophan. Tryptophan is the sole dietary precursor for the synthesis of serotonin and melatonin, two signaling molecules that play central roles in sleep initiation, circadian rhythm regulation, and mood stability. Both human mother’s milk and alpha-lactalbumin supplementation have been shown to raise circulating plasma tryptophan levels, a change associated with increased serotonin production and improvements in sleep-related outcomes [1].

Human research suggests that modest doses of tryptophan can meaningfully influence sleep onset. Supplementation with approximately 1 gram of tryptophan taken about 45 minutes before bedtime has been shown to reduce sleep latency in individuals with mild insomnia or prolonged time to fall asleep, although these effects are less consistent in more severe insomnia [2]. Importantly, tryptophan consumed in doses of 1 to 2 grams at bedtime is typically fully metabolized by morning, minimizing next-day sleep inertia and supporting a smooth transition from sleep to wakefulness [2].

How Tryptophan Metabolism Links to Melatonin

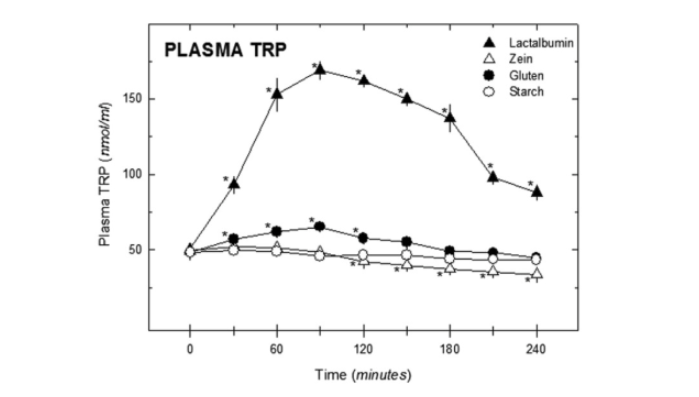

Sleep quality and circadian regulation depend on a tightly regulated biochemical pathway linking tryptophan, serotonin, and melatonin. After entering the brain, tryptophan is converted to 5-hydroxytryptophan and subsequently to serotonin [9]. In the pineal gland, serotonin is further acetylated and methylated to produce melatonin, the hormone that signals nighttime, coordinates circadian rhythms, and facilitates sleep onset and maintenance.

Figure 2. Tryptophan, Serotonin, Melatonin Synthesis Pathway. Dietary tryptophan from whole foods, human milk, or supplementation is transported into the brain, where it is metabolized into serotonin and, subsequently, melatonin, supporting mood regulation, circadian signaling, and sleep physiology.

Despite its importance, the primary rate-limiting step in melatonin production is not tryptophan intake itself, but tryptophan transport across the blood–brain barrier. Tryptophan shares transport mechanisms with other large neutral amino acids, including leucine, isoleucine, valine, tyrosine, and phenylalanine. These amino acids compete for the same transporters, meaning that the relative balance of tryptophan to competing amino acids often determines how much ultimately reaches the brain.

This competitive dynamic explains why the common belief that a glass of milk before bed improves sleep due to its tryptophan content is largely unsupported. Bovine milk contains relatively low absolute amounts of tryptophan, and its amino acid profile favors competition from other large neutral amino acids, limiting tryptophan transport into the brain and falling below the threshold required for meaningful sleep effects [9]. Similarly, high-protein meals can paradoxically reduce brain tryptophan availability when the accompanying amino acids outcompete tryptophan for transport.

Alpha-lactalbumin alters this equation. Its amino acid composition provides a higher relative concentration of tryptophan, increasing the likelihood that sufficient tryptophan reaches the brain despite competing amino acids.

Tryptophan Supplementation

Supplementation strategies aim to increase the tryptophan-to-large neutral amino acid ratio, thereby enhancing serotonin synthesis and downstream melatonin production. Alpha-lactalbumin is uniquely suited for this purpose due to its exceptionally high tryptophan content relative to other protein sources. This composition allows for greater tryptophan uptake into the brain even in the presence of competing amino acids [1][9].

Research indicates that alpha-lactalbumin supplementation can increase brain tryptophan availability by approximately 130 percent before bedtime [9]. While an exact optimal dose has not been established, available data suggest that sleep-related benefits are more consistently observed when tryptophan intake exceeds 1 gram. Increasing tryptophan intake beyond this threshold has been shown to reduce wake after sleep onset by approximately 50 percent, decreasing nocturnal wake time from over 56 minutes to less than 29 minutes [9]. Achieving these effects requires sufficient relative tryptophan intake to overcome competitive inhibition from other amino acids, a condition more readily met with alpha-lactalbumin supplementation.

Through these mechanisms, alpha-lactalbumin may support serotonin-mediated calmness in the evening and facilitate the rise in melatonin required for smooth sleep onset and sustained sleep maintenance.

Research indicates that alpha-lactalbumin supplementation can increase brain tryptophan availability by approximately 130 percent before bedtime

Does This Differ from Melatonin Supplementation?

Melatonin levels naturally decrease with age, particularly after the fourth decade of life, a change that may contribute to increased sleep fragmentation and insomnia. By age 70, circulating melatonin levels are estimated to be approximately 10 percent of peak prepubertal levels [12].

Melatonin supplementation is therefore a common strategy for improving sleep. Meta-analyses of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in select populations with insomnia indicate that melatonin supplementation can reduce sleep onset latency, increase total sleep time, and decrease nocturnal awakenings [12]. However, results across studies are mixed, and dosing strategies vary widely, with effective doses reported between 1 and 9 milligrams [13].

While melatonin supplementation offers a direct means of influencing sleep timing, tryptophan-based strategies may provide broader physiological effects. By supporting endogenous serotonin and melatonin synthesis, tryptophan intake has the potential to influence mood regulation, stress resilience, and metabolic function in addition to sleep outcomes, suggesting a more integrative approach to sleep support.

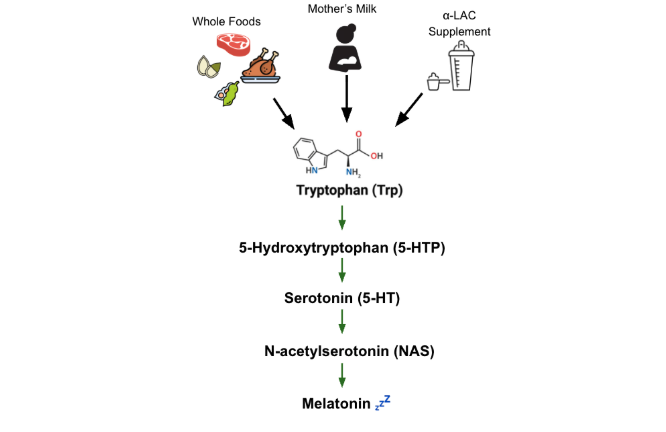

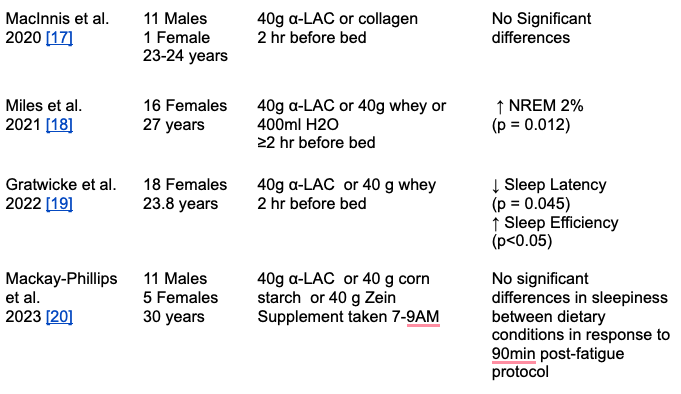

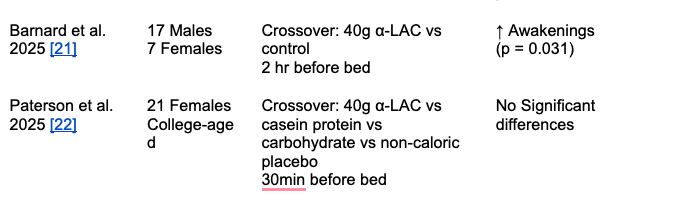

Alpha-Lactalbumin Supplementation for Sleep

Although alpha-lactalbumin is not a sedative, it appears to influence sleep quality by shaping the biochemical environment that supports serotonin and melatonin synthesis. This effect is driven primarily by its high relative tryptophan content. Controlled human studies demonstrate that alpha-lactalbumin supplementation can increase circulating plasma tryptophan concentrations by as much as threefold, a magnitude sufficient to meaningfully alter the tryptophan pool available for transport into the brain (Figure 3) [1][14]. Because brain serotonin synthesis is sensitive to changes in tryptophan availability, this rise in plasma tryptophan is thought to support smoother sleep onset and improved sleep continuity.

Figure 3. Plasma Tryptophan Response to Alpha-Lactalbumin Versus Carbohydrates. 40 g of alpha-lactalbumin increases plasma tryptophan concentration 3-fold. Adapted from “The ingestion of different dietary proteins by humans induces large changes in the plasma tryptophan ratio, a predictor of brain tryptophan uptake and serotonin synthesis” Fernstrom et al. 2013, Clinical Nutrition, Volume 32 (Issue 6), 1073–1076.

Figure 3 illustrates the distinct plasma tryptophan response following ingestion of alpha-lactalbumin compared with carbohydrate and other protein sources. In this study, a 40-gram dose of alpha-lactalbumin produced a rapid and sustained elevation in plasma tryptophan that far exceeded responses observed with starch, gluten, or zein proteins. Importantly, this response reflects not only total tryptophan intake, but the favorable tryptophan-to-competing amino acid ratio characteristic of alpha-lactalbumin, a key determinant of brain tryptophan availability [1].

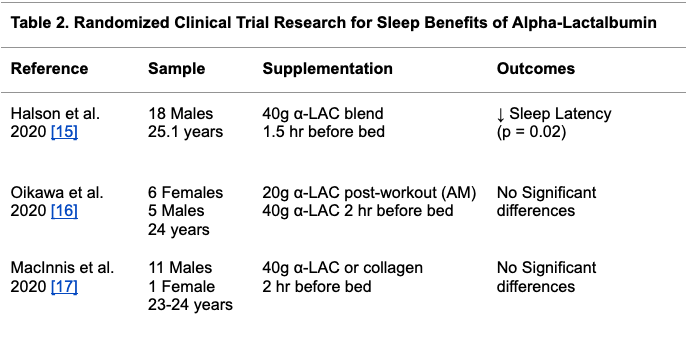

Despite these clear biochemical effects, clinical outcomes related to sleep have been variable. Several randomized trials report improvements in sleep latency, sleep efficiency, or next-day alertness following alpha-lactalbumin supplementation [15][18][19], while others observe neutral effects on sleep measures [16][17][22]. This variability does not negate the underlying mechanism, but rather highlights the importance of contextual factors such as dose, timing, energy intake, and participant characteristics.

A closer examination of recent randomized trials between 2020 and 2025 reveals a consistent methodological pattern. Most studies administered relatively large bolus doses of 40 grams of alpha-lactalbumin approximately two hours before intended bedtime [14]. At this dose, alpha-lactalbumin provides at least 160 kilocalories, an energy load that may, in turn, influence sleep onset and overnight physiology. In addition, although alpha-lactalbumin is rich in tryptophan relative to other proteins, a 40-gram serving typically provides less than 2 grams of tryptophan, with less than 1 gram per 20-gram equivalent serving. This may limit the extent to which tryptophan transport across the blood–brain barrier is enhanced under conditions of amino acid competition [14][21].

These factors suggest that both timing and energy intake may modulate the observable effects of alpha-lactalbumin on sleep. Smaller servings closer to 20 grams reduce pre-sleep caloric intake to under 100 kilocalories, a range more consistent with sleep-promoting nutritional strategies. Supporting this interpretation, one randomized, crossover trial from Dr. Mike Ormsbee’s laboratory differed notably from earlier studies by administering alpha-lactalbumin 30 minutes before sleep rather than 2 hours prior [22]. While this study did not demonstrate significant group-level differences in sleep outcomes, it underscores the emerging importance of supplementation timing relative to circadian physiology.

Taken together, these findings suggest that alpha-lactalbumin’s sleep-related effects are not solely dose-dependent, but are shaped by the interaction between tryptophan availability, energy intake, and proximity to sleep onset. It is therefore plausible that formulations emphasizing higher relative tryptophan content, lower total caloric load, and ingestion closer to bedtime may better leverage alpha-lactalbumin’s biochemical advantages. Rather than contradicting the underlying mechanism, mixed clinical outcomes highlight the need for more precise alignment between amino acid biology and sleep physiology.

Energy Intake, Macronutrients, and Timing for Sleep Optimization

A recent publication, entitled "Nutrition Strategies to Promote Sleep in Elite Athletes: A Scoping Review," reviewed the research literature for evidence-based strategies to improve sleep. Many strategies were analyzed; however, this valuable scoping review provides four key notes regarding energy and protein intake for sleep optimization.

Increases in evening energy intake can slow sleep transition (sleep onset latency)

One of the clearest findings was that excessive evening energy intake can impair sleep initiation. Across studies, each additional megajoule of energy, approximately 240 kilocalories, consumed in the evening was associated with a five-minute increase in sleep onset latency (p = 0.011) [24]. This suggests that the total caloric load near bedtime plays a meaningful role in delaying the transition to sleep, likely through effects on thermogenesis, digestion, and metabolic signaling.

- Increasing evening protein intake can improve sleep transition (sleep onset latency)

The review highlighted that protein intake exerts a distinct and often opposing effect. Increasing evening protein intake was associated with faster sleep onset, with each additional gram of protein per kilogram of body weight reducing sleep latency by approximately 2 minutes (p = 0.013) [24]. This finding underscores that sleep outcomes are shaped not only by total energy intake but also by macronutrient composition, with protein exerting effects that differ from those of carbohydrate or fat.

- Sleep duration is reduced by increasing the time between the last food/drink and bedtime.

Timing also emerged as a critical variable. Longer intervals between the final intake of food or drink and bedtime were associated with shorter total sleep duration; each additional hour of fasting before sleep reduced total sleep time by approximately 6 minutes (p = 0.014) [24]. Together, these findings suggest that both excessive caloric intake too close to bedtime and prolonged fasting before sleep may be counterproductive, pointing instead toward a narrower nutritional window in which modest, protein-focused intake may be optimal.

- People who naturally sleep better consume more energy, protein, and tryptophan

Interestingly, the review also found that individuals classified as “good sleepers” tended to consume more total energy, protein, and tryptophan throughout the day than poorer sleepers (p < 0.05) [24]. This observation reinforces the idea that sleep quality reflects cumulative nutritional patterns rather than isolated interventions, and that adequate protein and amino acid intake may support sleep physiology when appropriately timed.

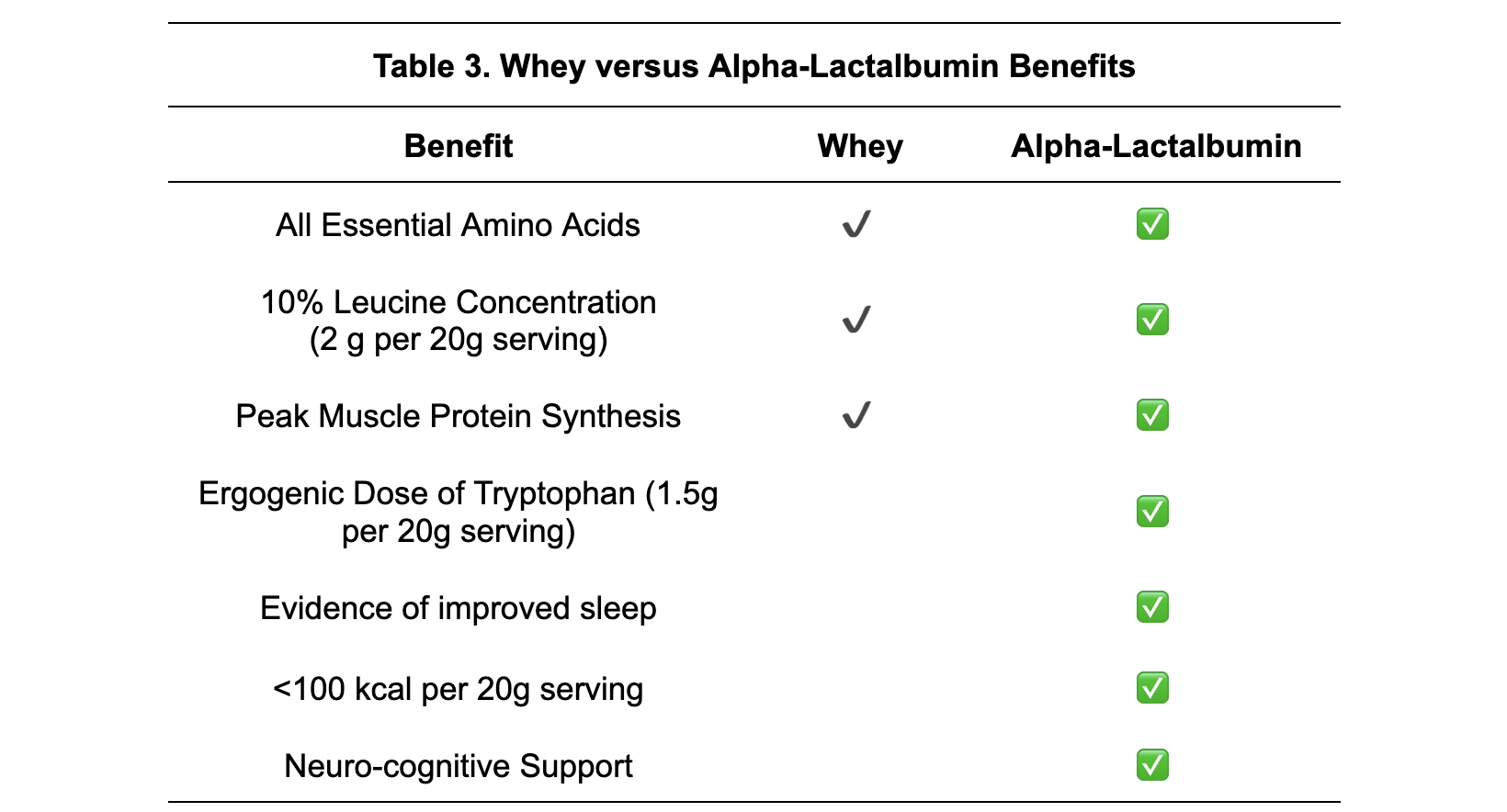

Healthspan’s alpha-lactalbumin supplement was formulated with these principles in mind. Each 20-gram serving provides a relatively high dose of tryptophan, approximately 1.5 grams, while keeping total energy intake below 100 kilocalories. This formulation allows for meaningful tryptophan delivery without the caloric burden associated with larger protein boluses. To maximize potential sleep benefits, consumption closer to intended bedtime may better align amino acid availability with circadian sleep signaling.

Metabolic Health and Body Composition Effects

Evening protein intake has long been debated, particularly regarding its potential impact on fat metabolism. However, accumulating evidence suggests that small, high-protein snacks consumed before bed support overnight muscle protein synthesis and contribute to muscle preservation and adaptation following exercise training [25][26]. In addition to supporting muscle repair, pre-sleep protein supplementation has been shown to increase overnight metabolic rate and promote satiety, even when total daily energy intake is held constant [27].

Macronutrient composition is particularly important in this context. High-protein, low-carbohydrate evening snacks have been shown to elicit more favorable glucose and insulin responses than lower-protein alternatives [26]. This is especially relevant for individuals with impaired insulin sensitivity, for whom late-evening carbohydrate intake may exacerbate metabolic dysregulation.

Preclinical research further supports a metabolic role for alpha-lactalbumin. In animal models, once-daily alpha-lactalbumin supplementation was protective against metabolic dysfunction, reducing body weight, blood glucose, insulin levels, and HOMA-IR despite consumption of a high-fat diet [28]. These findings suggest that alpha-lactalbumin may exert metabolic benefits beyond its role as a protein source.

Insulin resistance is a widespread metabolic challenge and a central feature in many cases of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). In women with PCOS, even small doses of alpha-lactalbumin, as low as 50 milligrams, combined with myo-inositol at 2 grams, produced significant improvements in body weight, ovulation rates, and menstrual cycle regularity. These effects exceeded those observed with myo-inositol alone, highlighting alpha-lactalbumin’s role as a synergistic agent in metabolic and reproductive health [29]. Additional human studies support the benefits of alpha-lactalbumin supplementation for gut microbiome balance, insulin sensitivity, and reduced intestinal inflammation, all of which contribute to improved metabolic health in PCOS and related conditions [29][30].

More broadly, systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate that high-quality protein sources rich in essential amino acids are associated with improvements in lipid profiles and reductions in cardiometabolic risk [31]. Similar to whey protein, alpha-lactalbumin is rich in branched-chain amino acids, including leucine, isoleucine, and valine. Its natural leucine content exceeds that of egg, soy, beef, and most plant-based protein sources [1]. Both preclinical and clinical research demonstrate that dairy protein supplementation, including alpha-lactalbumin, supports metabolic health and favorable changes in body composition by promoting energy balance and satiety [1][31][32][33].

Taken together, these metabolic effects position alpha-lactalbumin as a particularly suitable protein source for evening and recovery-focused nutrition. Its ability to support muscle repair, metabolic efficiency, and insulin sensitivity while minimizing excessive caloric and glycemic load makes it well aligned with the physiological demands of the pre-sleep period.

Cognitive and Mood Support

Beyond sleep and metabolic health, alpha-lactalbumin’s high tryptophan content supports central serotonin production, with implications for mood stability, mental clarity, and cognitive performance. Serotonin plays a central role in regulating emotional tone, stress responsiveness, attention, and cognitive flexibility, linking amino acid availability to both psychological and behavioral outcomes. By increasing circulating tryptophan and favoring its transport into the brain, alpha-lactalbumin may influence these neurochemical pathways in a manner distinct from other protein sources.

Human studies suggest that alpha-lactalbumin ingestion may support sustained attention and cognitive performance the following morning, particularly under conditions of sleep restriction, circadian disruption, or elevated cognitive demand [21][34]. These effects may be especially relevant for populations such as shift workers, frequent travelers, athletes, and individuals exposed to chronic psychological stress, for whom both sleep quality and cognitive resilience are frequently compromised. In these contexts, alpha-lactalbumin appears to influence not only recovery nutrition but also next-day neurocognitive readiness.

Alpha-lactalbumin has also been studied in relation to central fatigue, a phenomenon characterized by declining cognitive and motor performance during prolonged physical or mental exertion. Central fatigue is influenced in part by changes in brain serotonin signaling, particularly during sustained effort. By modulating serotonin availability, alpha-lactalbumin may attenuate aspects of central fatigue, supporting endurance, cognitive persistence, and perceived effort during prolonged tasks [21][34][35]. These neuromodulatory effects appear most pronounced in individuals with underlying psychological strain, sleep disruption, or advancing age, suggesting a context-dependent benefit.

Another emerging dimension of alpha-lactalbumin’s neurophysiological effects involves pain perception and recovery. A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis reported that higher tryptophan and serotonin levels were associated with reduced pain sensitivity and improved subjective well-being, particularly in individuals experiencing sleep disturbances or high training loads [36]. Because pain perception, mood regulation, and sleep quality are tightly interlinked, these findings support a broader role for tryptophan-rich nutrition in recovery and psychological resilience.

Taken together, these findings position alpha-lactalbumin as more than a conventional muscle-building protein. Its influence on serotonin-mediated pathways allows it to bridge physical recovery with mental performance, stress regulation, and cognitive function, reinforcing the concept that nutritional strategies targeting amino acid signaling can shape both body and brain outcomes.

Practical Applications

Alpha-lactalbumin represents a meaningful step forward in protein supplementation, combining the anabolic potency traditionally associated with whey protein with additional benefits related to sleep regulation, metabolic efficiency, and cognitive function. Unlike conventional protein supplements that are optimized primarily for muscle repair, alpha-lactalbumin’s physiological effects extend across multiple interconnected systems, reflecting the influence of its unique amino acid profile rather than total protein content alone.

By delivering sufficient leucine to activate muscle protein synthesis while simultaneously providing a high relative concentration of tryptophan, alpha-lactalbumin supports both tissue repair and neurochemical pathways involved in sleep, mood regulation, and stress resilience. This dual functionality allows it to operate across the full day–night cycle, supporting recovery, metabolic health, and cognitive readiness rather than targeting a single outcome in isolation. Its favorable tryptophan-to-competing amino acid ratio further distinguishes alpha-lactalbumin from other protein sources, enabling more effective support of endogenous serotonin and melatonin synthesis.

From a practical standpoint, alpha-lactalbumin can be incorporated flexibly into daily nutrition strategies. When consumed post-exercise, it provides anabolic signaling comparable to whey protein, supporting muscle repair and adaptation. When consumed closer to bedtime, smaller servings with higher relative tryptophan content may function as a pre-sleep recovery tool, supporting sleep physiology without imposing excessive caloric or glycemic load. This versatility makes alpha-lactalbumin particularly well-suited for individuals seeking to align nutrition with circadian biology, including athletes, aging adults, shift workers, and those managing metabolic or sleep-related challenges.

Beyond its role in muscle recovery and sleep support, alpha-lactalbumin contributes to broader aspects of metabolic and cognitive health. Evidence linking its use to improved insulin sensitivity, favorable body composition, enhanced satiety, and neurocognitive performance highlights its potential as a metabolically healthy protein source. These effects reinforce the concept that protein quality, timing, and amino acid composition can meaningfully influence long-term healthspan rather than serving solely as short-term recovery aids.

While the existing body of research supports alpha-lactalbumin’s multifunctional potential, further investigation is needed to fully delineate optimal dosing strategies, timing, and population-specific applications. Healthspan remains committed to advancing this research, integrating emerging scientific evidence with clinical insight to refine nutritional strategies that support longevity, resilience, and whole-body health. By leveraging the evolving science of protein supplementation, alpha-lactalbumin offers a promising foundation for multidimensional healthspan optimization.

- Applications for α-lactalbumin in human nutrition — Layman DK; Lönnerdal B; Fernstrom JD (2018)

- Is tryptophan a natural hypnotic? — Young SN (1986)

- Investigating the Health Implications of Whey Protein Consumption: A Narrative Review of Risks, Adverse Effects, and Associated Health Issues — Cava E et al. (2024)

- Is leucine content in dietary protein the key to muscle preservation in older women? — Volpi E (2018)

- Evaluating the Leucine Trigger Hypothesis to Explain the Post-prandial Regulation of Muscle Protein Synthesis in Young and Older Adults: A Systematic Review — Zaromskyte G et al. (2021)

- Fast whey protein and the leucine trigger: effects on exercise-induced muscle protein synthesis — Burd NA; Phillips SM (2010)

- Amino Assets: How Amino Acids Support Immunity — Kelly T et al. (2020)

- Glutathione: overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis — Forman HJ; Zhang H; Rinna A (2009)

- The impact of tryptophan supplementation on sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis — Sutanto CN et al. (2021)

- Tryptophan metabolism in health and disease — Gabela AM et al. (2025)

- Tryptophan-enriched cereal intake improves sleep, melatonin, serotonin, and antioxidant capacity in elderly humans — Bravo R et al. (2012)

- Melatonin in sleep disorders — Poza JJ et al. (2022)

- Melatonin for disordered sleep in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review — Guénolé F et al. (2011)

- Alpha-lactalbumin and sleep: a systematic review — Authors listed in PubMed record (2024)

- Optimisation and validation of a nutritional intervention to enhance sleep quality and quantity — Halson SL et al. (2020)

- Lactalbumin, not collagen, augments muscle protein synthesis with aerobic exercise — Authors listed in PubMed record (2020)

- Presleep α-lactalbumin consumption does not improve actigraphy-based indices of sleep quality or cycling performance — MacInnis MJ et al. (2020)

- α-Lactalbumin improves sleep and recovery after simulated evening competition in female athletes — Miles KH et al. (2021)

- The effect of α-lactalbumin consumption on sleep quality and quantity in female rugby union athletes — Gratwicke M et al. (2023)

- Effects of α-lactalbumin on strength, fatigue, and psychological parameters: a randomized double-blind crossover study — Mackay-Phillips K et al. (2023)

- Evening alpha-lactalbumin supplementation alters sleep, recovery, and performance measures — Barnard J et al. (2025)

- Pre-sleep milk-derived proteins do not impair sleep or recovery in elite female athletes — Paterson KGP et al. (2025)

- Exploring the serotonin–probiotics–gut health axis: a review of current evidence — Akram N et al. (2023)

- Nutrition strategies to promote sleep in elite athletes — Rackard G et al. (2025)

- The impact of pre-sleep protein ingestion on the skeletal muscle adaptive response to exercise in humans — Snijders T et al. (2019)

- Protein ingested before sleep increases overnight muscle protein synthesis rates in healthy older men — Kouw IWK et al. (2017)

- Pre-sleep protein supplementation affects energy metabolism and appetite in sedentary healthy adults — Hao Y et al. (2022)

- Bovine α-lactalbumin hydrolysates ameliorate metabolic and inflammatory disturbances — Gao J et al. (2018)

- Comparing the efficacy of myo-inositol plus α-lactalbumin versus myo-inositol alone in patients with PCOS — Kamenov Z et al. (2023)

- Positive effects of α-lactalbumin in the management of metabolic and inflammatory conditions — Cardinale V et al. (2022)

- Effects of whey protein supplementation on indices of cardiometabolic health — Prokopidis K et al. (2024)

- Whey protein components lactalbumin and lactoferrin improve energy balance and metabolism — Zapata RC et al. (2017)

- Milk protein for improved metabolic health — McGregor RA et al. (2013)

- Whey protein rich in α-lactalbumin increases plasma tryptophan ratio and improves cognitive performance in stress-vulnerable subjects — Markus CR et al. (2001)

- Diet rich in α-lactalbumin improves memory in unmedicated recovered depressed patients and matched controls — Booij L et al. (2006)

- The role of tryptophan and its derivatives in musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis — Canales GDLT et al. (2024)

Related studies