The Neuroprotective and Longevity Potential of Low-Dose Lithium

Prefer to listen? Hit play for a conversational, audio‑style summary of this article’s key points.

Lithium may be more than a psychiatric drug—it may function as a brain-relevant micronutrient. Trace lithium is present in food and water, and emerging evidence suggests that physiologic lithium availability may support neuronal integrity and cognitive resilience across aging.

A 2025 Nature study linked early Alzheimer’s biology to declining endogenous brain lithium. In post-mortem human tissue, cortical lithium was highest in cognitively healthy brains and progressively lower in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease, and lithium was the only statistically significant metal alteration observed in both MCI and AD among 27 metals measured.

Environmental lithium exposure correlates with longevity signals—without proving causality. In Oita Prefecture, Japan, a study across 18 municipalities (~1.2 million residents) found that tap water lithium ranged from 0.7 to 59 μg/L, and higher lithium levels were associated with lower all-cause mortality, even after adjusting for suicide rates.

Low-dose lithium may act “upstream” of multiple Alzheimer’s-linked processes. Lithium inhibits GSK-3β, a regulatory kinase that, when overactive, promotes tau phosphorylation and biases cells toward increased amyloid-β production—two converging molecular pressures in neurodegeneration.

Human clinical signals suggest lithium can engage Alzheimer’s-relevant biology at sub-psychiatric doses. In Forlenza’s MCI trial, lithium carbonate dosed to a serum range of 0.25–0.5 mmol/L (below typical psychiatric targets) was associated with lower CSF phosphorylated tau after 12 months and a slower rate of cognitive decline vs placebo on standard cognitive/functional scales.

Even “microdose” lithium has shown provocative cognitive stabilization in a small AD study. In a 2013 trial, patients with Alzheimer’s disease received 300 micrograms/day of elemental lithium for 15 months; the lithium group remained roughly stable on MMSE, while placebo declined from ~20 to ~14, consistent with substantial clinical progression over the same period.

Formulation and delivery may matter as much as dose—especially in the presence of amyloid. Amyloid-β plaques can act as charged “sponges” that sequester lithium; in the 2025 Nature work, lithium orotate stood out among 16 lithium salts tested for being uniquely able to avoid plaque sequestration, offering a mechanistic explanation for why older Alzheimer’s trials with lithium carbonate may have produced inconsistent results.

Low-dose lithium is a different biological goal than psychiatric lithium—and blood tests can mislead. Typical psychiatric regimens deliver roughly 150–300 mg/day elemental lithium (often targeting 0.5–1.2 mmol/L serum). Low-dose approaches are commonly ~1–10 mg/day, where serum levels are often <0.2 mmol/L or even “undetectable,” making blood lithium more useful as a safety tool than a marker of brain sufficiency.

Dietary lithium intake is real but highly variable by geography. Typical total intake from food + water is estimated around ~0.5–3 mg/day, with some high-lithium water regions reaching ~5 mg/day or more; this contextualizes why 5–10 mg/day supplementation is often framed as approximating the upper end of natural exposure rather than pharmacologic dosing.

Precision tools are coming that could make lithium a “measurable” brain-health strategy. ⁷Li-MRI (Lithium-7 MRI) aims to map lithium distribution directly in brain tissue (currently mostly in research settings), potentially enabling early vulnerability detection, response monitoring, and individualized dosing based on brain availability rather than serum proxies.

Introduction: Lithium Beyond Psychiatry

Lithium occupies a singular position in medicine. Chemically simple, the third element on the periodic table, and the lightest solid metal, it has long been biologically consequential. For much of the past century, lithium has been defined almost exclusively as a pharmaceutical, prescribed at relatively high doses to stabilize mood in bipolar disorder. In that context, it has been viewed as a powerful but narrowly applied drug.

A growing body of research now points to a broader role. Beyond psychiatry, lithium is increasingly recognized as a trace element relevant to brain biology and cognitive resilience [1]. Small amounts occur naturally in soil and groundwater and enter the human diet primarily through drinking water. Although these exposures are far below clinically understood therapeutic doses, accumulating evidence suggests they may nonetheless be biologically meaningful [2].

This reframing was sharpened in 2025, when a study published in Nature, titled Lithium deficiency and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, identified a direct association between depletion of endogenous brain lithium and the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease [3]. These findings reposition lithium not merely as a treatment for disordered mood, but as a factor involved in maintaining neuronal integrity and resistance to age-related cognitive decline.

Together, these recent insights raise a central question: if trace-level lithium contributes to cognitive stability across the lifespan, could declining lithium availability represent an underappreciated risk factor for neurodegeneration and/or cognitive decline with aging? Second, might low-dose lithium support broad healthspan benefits?

In this review, we trace lithium’s evolution from psychiatric drug to potential geroprotective factor, examining its history, emerging mechanistic evidence, and population-level data linking environmental lithium exposure to cognitive resilience and longevity.

From Panacea to Psychiatric Drug and Back Again

Lithium’s medical history begins in the mid 19th century with the uric acid hypothesis of disease. Physicians believed that excess uric acid contributed not only to joint inflammation but also to psychiatric symptoms sometimes described as “brain gout” by impairing blood flow in small cerebral vessels [4]. Because lithium salts dissolved uric acid crystals in laboratory experiments, lithium was rapidly adopted as a broad therapeutic agent.

This discovery fueled the late 19th-century popularity of lithium-rich mineral waters and the ensuing “Lithia water” craze [5]. By the early 20th century, lithium had entered consumer culture, appearing in products such as the original formulation of 7-Up, which contained lithium citrate until regulatory bans in 1948 ended its use in foods and beverages [6].

Lithium’s applications narrowed in the mid-20th century. In 1949, Australian psychiatrist John Cade demonstrated its efficacy in treating acute mania, leading to FDA approval for bipolar disorder in 1970 [7]. At psychiatric doses, typically 600–1200 mg of lithium carbonate per day, lithium was highly effective but carried significant risks to kidney and thyroid function, cementing its reputation as a powerful but tightly monitored psychiatric drug.

Modern interest reflects a return to an older question, approached with modern tools: what role do trace amounts of lithium play in human biology? Environmental lithium exposure is roughly 100-fold lower in dose than pharmacological, yet still may influence cellular pathways involved in brain health and aging.

Early Signals of Longevity

The hypothesis that lithium may influence longevity emerged not from clinical trials, but from epidemiological studies examining health outcomes across regions with naturally varying lithium concentrations in drinking water [8,9]. While such studies cannot establish causation, consistent population-level associations provide valuable signals for targeted research investigation.

One of the most influential examples comes from Oita Prefecture, Japan. Across 18 municipalities encompassing more than 1.2 million residents, lithium concentrations in tap water ranged from 0.7 to 59 μg/L [8]. Higher lithium levels were associated with lower all-cause mortality, an effect that persisted even after adjusting for suicide rates [8].

Similar patterns have been observed elsewhere, driven largely by geological variation. In a study spanning 226 counties in Texas, higher lithium concentrations in public water supplies were associated with lower rates of suicide, homicide, and violent crime [9]. Although these outcomes reflect social and psychological dimensions of health, they are consistent with a broader stabilizing influence on brain function and stress responsiveness.

Laboratory data strengthened biological plausibility. Animal model research using round worms known as Caenorhabditis elegans, higher lithium exposure reduced mortality and extended lifespan by up to 36% [10]. Together, ecological and experimental findings suggest that lithium exposure can influence conserved pathways linked to stress resistance and aging.

These observations alone do not establish lithium as a longevity intervention in humans. They do, however, raise a compelling possibility that chronic exposure to low dose lithium may subtly enhance neurobiological resilience over time, especially when the lithium content in groundwater exposure from the environment is relatively low.

Encouraging Observational Human Longevity Data

Large observational datasets have been examined for human longevity signals, most notably the UK Biobank, which includes over 500,000 middle-aged and older adults [11]. Although some controversial evidence supports diverse longevity benefits in humans. Subsequent research efforts have examined more specific biological aging mechanisms. Based upon research in bipolar disorder patients, lithium might attenuate telomere shortening and thus have some genetic linkage to human longevity [12,13], yet a UK Biobank analysis of 591 lithium-treated individuals found no association with telomere length or frailty [14].

In 2023, a review focused on the benefits of low-dose lithium supplementation, beyond its psychiatric applications, touted the diverse impact it can have in prolonging healthspan [15].

These results suggest lithium’s benefits may provide distinct neuroprotective advantages in addition to broad suppression of systemic aging [15].

An Inflection Point: Lithium as an Essential Brain Element

In August 2025, a study led by Dr. Bruce Yankner and published in Nature provided direct evidence that lithium is an intrinsic component of human brain physiology [3]. Using post-mortem human tissue and experimental models, the researchers identified lithium depletion as one of the earliest molecular changes preceding Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [3].

This finding represents a conceptual shift. Alzheimer’s disease emerges not only as a disorder of toxic protein accumulation, but also as a state of critical micronutrient deficiency within vulnerable brain regions. If lithium loss is a potential initiating event rather than a downstream consequence, restoring physiological lithium levels may offer an exciting new avenue for preserving cognitive resilience.

Metallomic Analysis of the Brain

To explore this possibility, the Harvard team focused on metallomic analysis of brain tissue. Metallomic profiling of the brain had previously uncovered alterations in other metals observed in AD, including increased sodium and zinc and reduced copper [3]. However, decreased cortical lithium was the only statistically significant metal alteration observed in both mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD [3]. Among 27 metals measured, lithium was unique; it was the only element whose levels differed significantly at the earliest stage of cognitive decline, which may present an opportunity for action and correction.

In the prefrontal cortex, lithium concentrations were highest in cognitively healthy brains and progressively lower in MCI and AD. Other metals remained largely unchanged. Parallel experiments in mice showed that reduced brain lithium levels were associated with impaired performance on memory and learning tasks and applied cognitive tests [3]. These findings position lithium not as a bystander, but as a metal whose availability tracks tightly with long-term cognitive health.

The Amyloid Trap: Lithium Sequestration

Dr. Bruce Yankner and colleagues also addressed why lithium declines in the aging brain. As amyloid-β plaques accumulate, they sequester or “steal” lithium. Because amyloid plaques carry a negative charge, they attract and attract positively charged lithium ions, binding them within plaques while depriving surrounding neurons [3].

This creates a localized lithium deficiency at precisely the moment resilience mechanisms are most needed. This finding helps explain why prior AD trials using lithium carbonate produced inconsistent results: since the administered lithium may have been diverted and locked into plaques before reaching vulnerable neurons. Viewed this way, AD reflects not only toxic accumulation but also micronutrient misallocation, a feed-forward cycle that damages cognitive function.

Molecular Mechanisms of Neuroprotection

Lithium supports brain health by coordinating several processes that decline with age. Rather than targeting a single pathway, it acts as a systems regulator, maintaining balance across protein turnover, inflammation, and neural connectivity.

A central target is glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β)—an enzyme that functions as a cellular switchboard. In healthy cells, GSK-3β helps regulate energy metabolism, gene expression, and synaptic plasticity. It acts by adding phosphate groups to other proteins, subtly altering their activity. In the developing brain, this signaling is essential for growth and structural organization.

One way to conceptualize GSK-3β is as a dimmer switch within a vast electrical grid. In youth, it modulates signaling intensity with precision—brightening pathways needed for adaptation and learning while keeping baseline activity stable. The system remains flexible but controlled.

With age—and particularly in neurodegenerative disease—that dimmer can become biased upward. Instead of fine-tuning cellular signals, GSK-3β begins to amplify them.

When overactive, GSK-3β accelerates phosphorylation of tau, a structural protein that stabilizes microtubules inside neurons. Under normal conditions, phosphorylation is a reversible regulatory mark—akin to temporary scaffolding adjustments in a building. But excessive phosphorylation destabilizes the structure. Tau detaches from microtubules, misfolds, and aggregates, forming neurofibrillary tangles—one of the defining pathologies of Alzheimer’s disease.

GSK-3β also influences the processing of amyloid precursor protein, nudging cells toward increased amyloid-β production. As these processes accumulate, the consequences extend beyond individual molecules. Structural instability and protein aggregation begin to interfere with axonal transport, synaptic signaling, and cellular energy balance. What starts as subtle biochemical drift evolves into network-level dysfunction.

At the systems scale, this resembles rising electrical noise in a communication grid. Signals that once traveled cleanly between neurons become distorted. Synaptic timing falters. Microglia, sensing damage, shift toward chronic inflammatory states. The brain expends more energy maintaining baseline function and less on adaptation and memory formation.

Lithium inhibits GSK-3β, effectively easing this amplification [16]. Importantly, it does not appear to eliminate GSK-3β activity altogether—an essential consideration given the enzyme’s role in normal physiology. Instead, lithium recalibrates its activity toward a more physiologic range. By reducing aberrant tau phosphorylation and tempering amyloidogenic signaling, lithium may help lower molecular “noise” before widespread structural instability takes hold.

Its effects extend further. Lithium promotes autophagy—the cell’s intrinsic recycling system—enhancing clearance of damaged proteins and organelles that accumulate with age [17]. It preserves microglial function, restraining chronic neuroinflammation while supporting plaque clearance [18]. And it helps maintain myelin and synaptic integrity, preserving the physical wiring required for efficient neural communication [3]. Together, these mechanisms suggest that lithium operates upstream of multiple converging pressures of neurodegeneration. Rather than suppressing symptoms, it appears to support the brain’s intrinsic capacity for resilience.

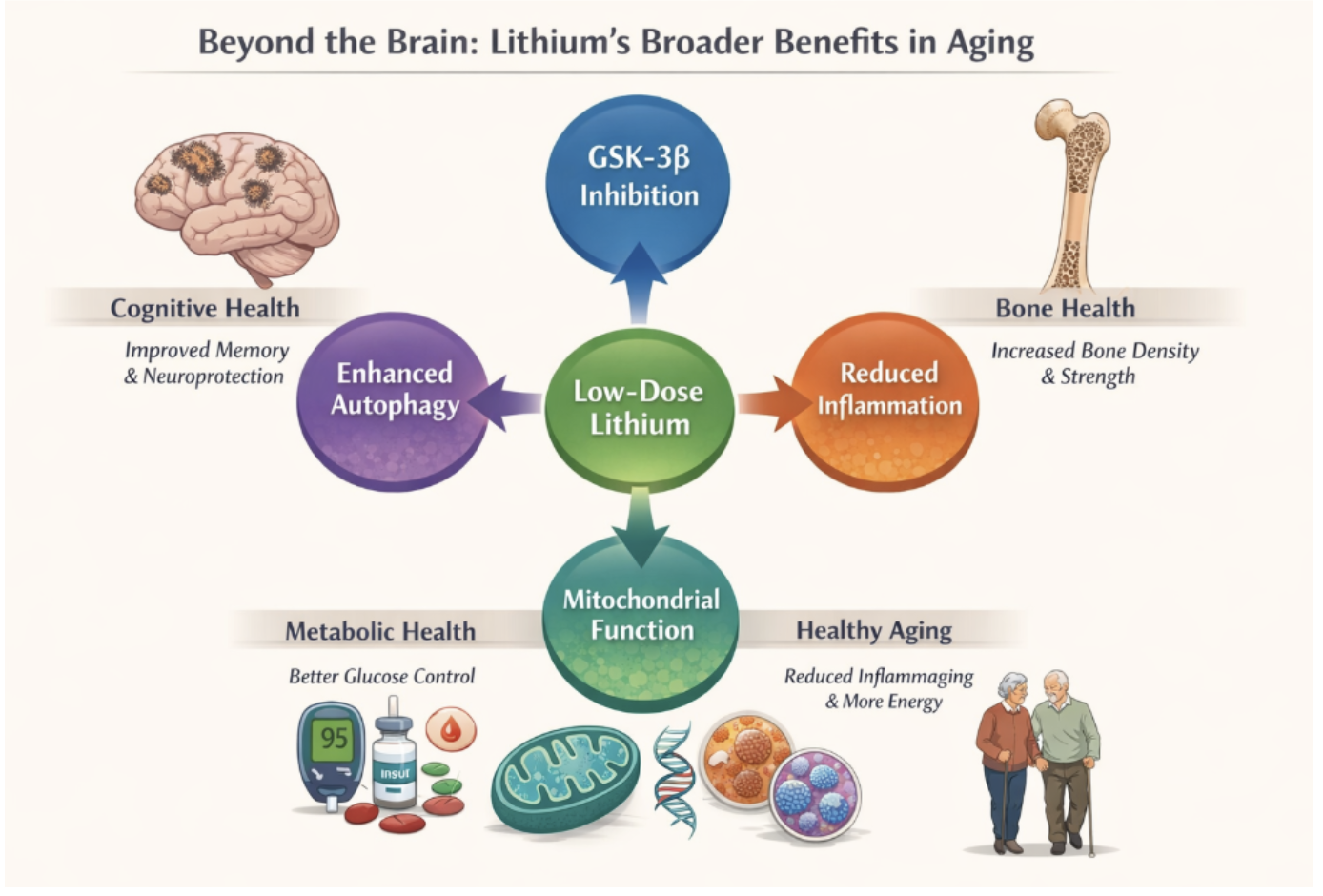

Beyond the Brain: Lithium as a Systems-Level Modulator of Aging

Although much of the recent focus on lithium has centered on cognitive health, the molecular pathways influenced by lithium are not unique to neurons. GSK-3β signaling, autophagy regulation, inflammatory tone, and mitochondrial efficiency are shared control points across multiple tissues that deteriorate with age [15]. This raises an important question: if lithium stabilizes these systems in the brain, might its effects extend to other domains of aging biology?

Emerging evidence suggests that this may be the case. Low-dose lithium exposure has been associated with improved bone density and reduced fracture risk, consistent with lithium’s inhibitory effect on GSK-3β—a pathway known to regulate osteoblast activity and bone formation [15]. Similarly, GSK-3β plays a central role in insulin signaling and glucose metabolism, offering a plausible mechanism by which lithium may support metabolic stability and glucose control in aging populations [15].

Lithium’s influence on autophagy and immune regulation also connects it to the biology of inflammaging the chronic, low-grade inflammation that accelerates tissue dysfunction with age [17]. By promoting cellular cleanup and tempering excessive inflammatory signaling, lithium may help preserve immune balance and reduce the cumulative burden of inflammatory damage across organs.

Finally, lithium’s effects on mitochondrial signaling and circadian regulation suggest potential relevance for cellular energy balance and fatigue resistance, aligning with observational reports of improved vitality and stress resilience at low doses. Importantly, these effects appear to emerge within physiological ranges, reinforcing the view of lithium not as a pharmacologic intervention, but as a modulator of several conserved aging pathways.

These promising biological applications suggest that lithium’s relevance to healthspan may not be confined to the brain alone. Instead, lithium appears to interact with core biological processes that govern aging across systems, with cognitive resilience representing one of the most sensitive and measurable outcomes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Lithium Broad Longevity Benefits

Comparative Pharmacokinetics: Why Lithium’s Salt Form and Dose Matter

One of the central challenges in translating lithium’s neuroprotective potential into practice is not whether lithium exerts meaningful biological effects, but how it is delivered to the brain. Much of lithium’s modern medical history is tied to lithium carbonate, the standard pharmaceutical form used in psychiatry [19]. While effective for mood stabilization, lithium carbonate was never designed for long-term brain maintenance or neurodegenerative prevention, and emerging evidence suggests it may be poorly suited for that role.

At the heart of this issue is pharmacokinetics, the study of how a compound is absorbed, distributed, and retained in the body [20]. For lithium to support cognitive health, it must not only enter the bloodstream, but also reach vulnerable neural tissue, remain bioavailable in the presence of pathology, and do so at doses low enough to avoid systemic toxicity. These requirements place unique constraints on both dose and salt form.

Lithium Is Never “Just Lithium”

Lithium is never administered as a free ion; it is always delivered bound to a carrier molecule, or salt. That carrier profoundly influences lithium’s absorption, tissue distribution, brain penetration, and safety profile. Much of the historical confusion surrounding lithium arises from the assumption that all lithium salts and all doses are biologically equivalent. They are not.

In psychiatric medicine, lithium is most commonly prescribed as lithium carbonate or lithium chloride, at doses designed to maintain stable, relatively high serum concentrations, typically between 0.6 and 1.2 mmol/L [15,20]. These salts dissociate readily in the bloodstream, releasing lithium ions that distribute broadly across tissues. This approach is effective for stabilizing mood, but it comes at a cost. Sustained systemic exposure places ongoing demands on renal and thyroid function, necessitating frequent blood monitoring. Importantly, the pharmaceutical-grade formulations were never optimized for selective brain delivery or for use at physiological, trace-level exposure.

Low-Dose Lithium: A Different Biological Goal

In contrast, interest in low-dose lithium for cognitive health and longevity is grounded in a fundamentally different objective, restoring optimal physiological lithium levels. This perspective draws inspiration from environmental and epidemiological data showing that populations exposed to higher naturally occurring lithium levels primarily through drinking water exhibit lower rates of neuropsychiatric disease and, in some cases, reduced all-cause mortality [8,9].

At these lower exposure levels, salt form becomes especially important. Among available options, lithium orotate has emerged as a candidate of particular interest [19]. Orotic acid is a naturally occurring molecule involved in pyrimidine synthesis and cellular transport. Early work proposed, and recent evidence supports, that this carrier may facilitate more efficient intracellular and brain uptake of lithium, even at much lower absolute doses [19].

Dose and Bioavailability: Not Simply “Less Lithium”

Low-dose lithium supplementation does not aim to replicate psychiatric lithium exposure at a smaller scale. Instead, it seeks to approximate environmental and nutritional exposure levels more closely aligned with human evolutionary biology.

Therapeutic psychiatric regimens typically deliver 150–300 mg of elemental lithium per day, whereas low-dose approaches generally provide a stark contrast in dose of only 1–10 mg of elemental lithium. At these levels, serum lithium concentrations may be undetectable or near the lower limit of standard laboratory assays [15], yet biological effects, particularly within the brain, may still occur.

This divergence underscores a critical principle that serum lithium concentration is a safety marker, not a reliable indicator of brain lithium sufficiency, especially at low doses. Brain availability depends on several factors, including transport, tissue binding, pathology, and salt form factors not captured by peripheral blood measurements.

The Reemergence of Lithium Orotate

Lithium orotate was first introduced in the 1970s by German physician Hans Nieper, who proposed that binding lithium to orotic acid could enhance its ability to cross biological membranes, including the blood–brain barrier [19]. Early interest in this compound waned, largely due to concerns about kidney toxicity when psychiatric-equivalent doses were extrapolated without appropriate pharmacokinetic data.

Importantly, these concerns arose before modern dose optimization, biomarker-guided safety monitoring, or an appreciation for lithium’s potential role at trace, physiological levels. Recent work has revived interest in lithium orotate, but with a crucial distinction: a focus on low-dose, long-term exposure designed to support brain resilience rather than treat acute psychiatric illness.

Evading the Amyloid Trap

The renewed relevance of lithium orotate became especially clear recently, where researchers tested 16 different lithium salts; lithium orotate stood out for a specific and unexpected reason: it was uniquely capable of avoiding sequestration by amyloid-β plaques [3].

As described earlier, amyloid plaques act as molecular “sponges,” binding lithium and preventing it from reaching surrounding neurons. Lithium orotate’s chemical properties appeared to reduce this binding, allowing lithium to remain bioavailable to healthy brain tissue even in the presence of established pathology. This finding provides a mechanistic explanation for why traditional lithium formulations may have failed to show consistent benefit in Alzheimer’s trials, not because lithium lacked neuroprotective potential, but because it could not reach its intended targets.

Potency at Lower Doses and Improved Safety Signals

Animal studies further highlight meaningful differences between lithium salts. In a mouse model of mania, lithium orotate achieved near-complete therapeutic effects at doses as low as 1.5 mg/kg, whereas lithium carbonate required 10–15 times higher doses to produce even partial effects [20]. This dramatic difference suggests more efficient tissue delivery and treatment outcomes.

Equally important are safety signals. In the same studies, lithium carbonate induced markers of renal stress, including excessive thirst and elevated creatinine within just two weeks of treatment [20]. Lithium orotate, by contrast, showed no evidence of kidney toxicity, even when administered at several times its effective dose [20]. These findings point to a substantially wider therapeutic window, a critical consideration for any compound intended for long-term use in aging populations.

Implications for Cognitive Healthspan

Taken together, these data suggest that lithium’s biological effects cannot be separated from its formulation. If lithium depletion contributes to neurodegeneration, then restoring physiological lithium levels safely and effectively will require delivery strategies that prioritize brain bioavailability over saturation or higher dosing strategies.

Lithium orotate is not a solution on its own, nor a substitute for rigorous human trials. But it illustrates that targeting brain aging, how a compound reaches neural tissue may matter as much as (or more than) what the compound is provided. As research continues, salt form and dosing strategy are likely to play a decisive role in determining whether lithium’s promise as a cognitive healthspan modulator can be realized safely.

Clinical Evidence: From Microdoses to Cognitive Stabilization

Although much of the strongest mechanistic evidence for lithium’s neuroprotective effects comes from animal models and post-mortem human tissue, several small but informative human trials have already explored whether low-dose lithium can influence cognitive decline. While these studies were not designed to prove disease modification, they offer early clinical insight into lithium’s potential to stabilize key features of neurodegeneration.

The Forlenza Mild Cognitive Impairment Trials

One of the most frequently cited examples comes from a series of studies led by psychiatrist Orestes Forlenza beginning in 2019 [21]. In an initial randomized trial, 45 individuals diagnosed with MCI, often considered a preliminary stage of AD assigned to receive either a placebo or low-dose lithium carbonate. Importantly, dosing was intentionally conservative, targeting blood lithium levels between 0.25 and 0.5 mmol/L [21], well below the typical psychiatric range of 0.6–1.2 mmol/L [15].

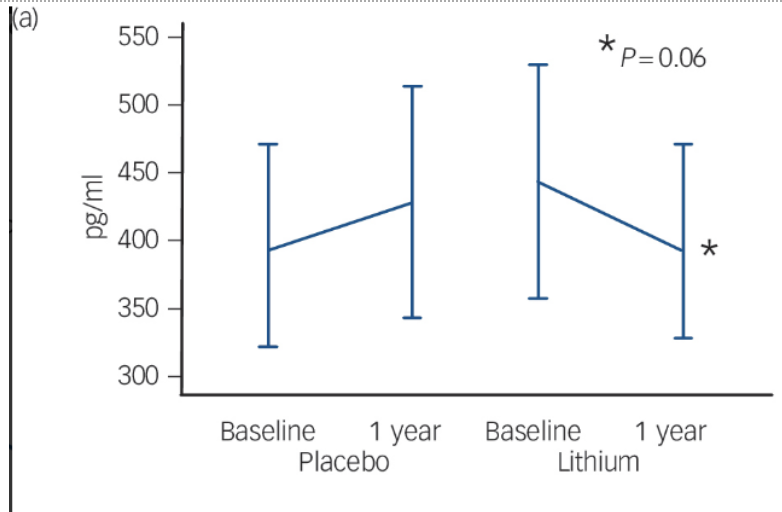

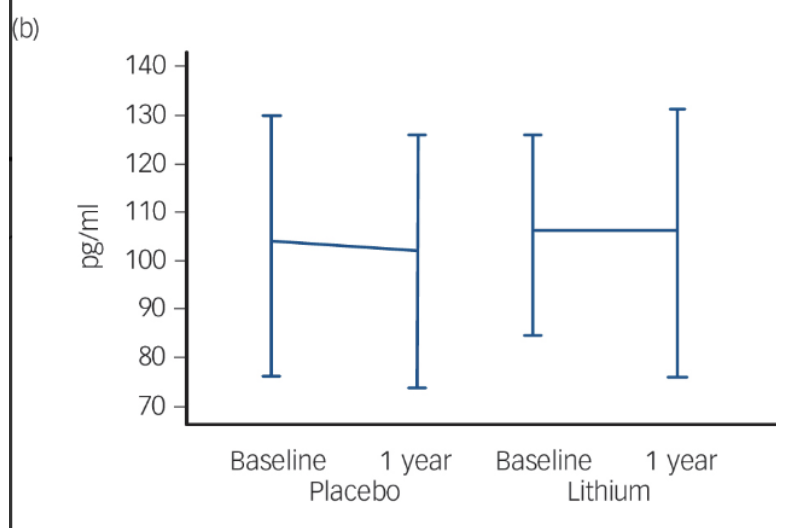

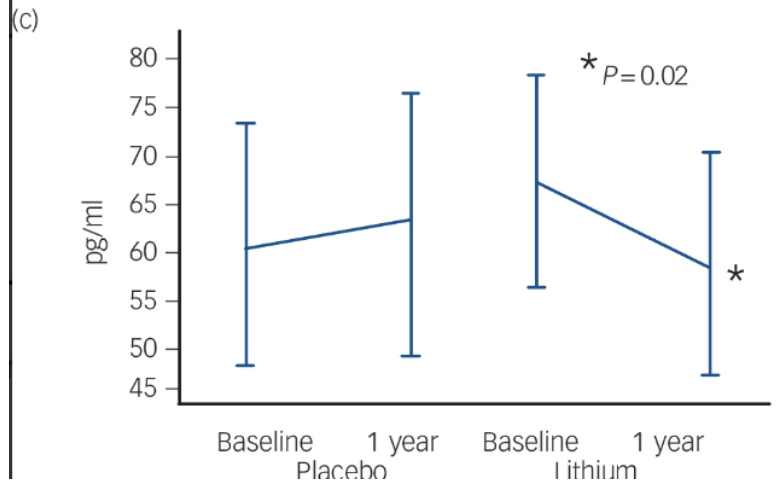

After 12 months of treatment, participants receiving lithium showed significantly lower levels of phosphorylated tau in their cerebrospinal fluid compared with the placebo group (Figure 2) [21]. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) bathes the brain and spinal cord and is commonly used as a window into ongoing neurodegenerative processes. Elevated phosphorylated tau and amyloid-β in CSF are both associated with disease progression and poorer prognosis in Alzheimer’s disease, making changes in these markers biologically meaningful.

Fig. 2 Changes in Brain Health Biomarkers Over 12 Months With Lithium

Comparison of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of patients taking a low-dose lithium treatment versus a placebo. (a) Amyloid-β42: This marker showed a slight decrease in the lithium group over one year (p = 0.06). (b) Total Tau: This is a general sign of nerve cell stress, which remained mostly unchanged in both the lithium and placebo groups. (c) Phosphorylated Tau: This is a "toxic" protein linked to the worsening of Alzheimer's Disease. The lithium group showed a significant reduction in this protein (p = 0.02), while the placebo group saw their levels rise. Reprinted from “Disease-modifying properties of long-term lithium treatment for amnestic mild cognitive impairment: randomised controlled trial”, by Forlenza, O. V. et al., 2011, The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science, 198(5), 351–356.

Clinical outcomes mirrored these biomarker findings. While all participants experienced some decline in daily functioning as measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR–SoB), the rate of cognitive deterioration was significantly slower in the lithium-treated group [21]. This effect was observed on the ADAS–Cog, a widely used test of memory, language, and problem-solving, as well as the SLN, which assesses attention and learning. In practical terms, lithium did not halt decline, but appeared to slow the pace at which cognitive abilities eroded.

Interpreting the Signal

Small trial data do not establish lithium as a definitive treatment for MCI or Alzheimer’s disease. However, they offer a critical proof of concept, even at doses far below psychiatric thresholds. Lithium can engage relevant disease pathways in humans, influencing both molecular markers of pathology and the trajectory of cognitive decline.

Viewed alongside recent mechanistic findings, the Forlenza trials suggest that lithium’s clinical effects may be most pronounced when used early before extensive neuronal loss has occurred and at doses that support physiological regulation rather than pharmacologic suppression. This reinforces the emerging view of lithium not as a conventional drug intervention, but as a potential modulator of cognitive resilience, particularly when applied during the earliest stages of neurodegeneration.

Microdose Signals in Alzheimer’s Disease

An even more provocative signal comes from a small clinical study conducted by Nunes and colleagues in 2013, which tested whether lithium could influence cognitive decline at doses far below those used in psychiatry [22]. In this trial, patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease received a daily microdose of just 300 micrograms of elemental lithium, thousands of times lower than standard therapeutic doses and comparable to the amount a person might ingest from naturally lithium-rich drinking water.

Despite the extremely low dose, the results were notable. Over a 15-month period, patients receiving lithium remained cognitively stable, as measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), a widely used assessment of global cognitive function [22]. In contrast, participants in the placebo group showed a marked decline, with MMSE scores falling from approximately 20 to 14, reflecting substantial loss of memory and functional capacity over the same period [22].

These findings do not suggest that microdose lithium reverses Alzheimer’s disease, nor do they establish it as a standalone therapy. However, they provide an important proof of principle: trace amounts of lithium can exert biologically meaningful effects on cognition when administered consistently over time. When viewed alongside ecological data and mechanistic insights, the study strengthens the case that lithium’s role in brain health may operate within a physiological range far below traditional pharmacologic dosing.

Integrating Lithium into a Longevity and Brain Health Strategy

As evidence accumulates, lithium is increasingly being discussed not as a treatment for a specific disease, but as a supporting element in the broader biology of brain aging. This reframing places lithium closer to other micronutrients that influence long-term resilience, important for maintaining function over decades, but not sufficient on their own to prevent disease.

From a longevity perspective, the most compelling interpretation is not that lithium “treats” neurodegeneration, but that adequate lithium availability may help preserve the molecular systems that resist it [3,15]. In this context, lithium becomes one component of a multifactorial strategy that includes physical activity, metabolic health, sleep, and cognitive engagement.

Dietary Sources and Supplemental Considerations

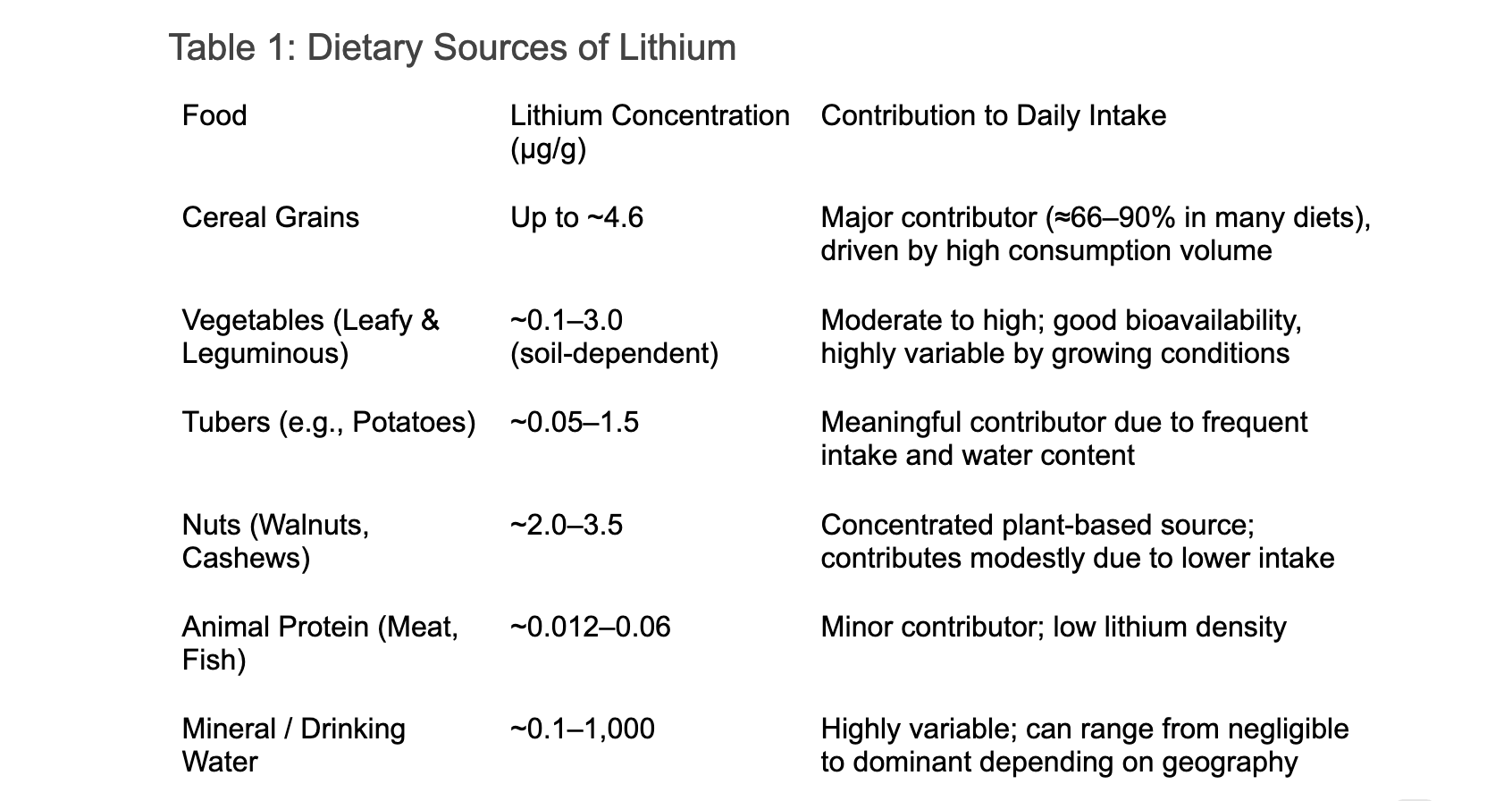

For most people, lithium exposure occurs through the diet. Grains, vegetables, and tubers, particularly leafy greens, bulbous vegetables, legumes, and potatoes, account for an estimated 66–90% of daily lithium intake [2]. Additional trace amounts are found in nuts and seeds, as well as in certain animal products such as fish and meat. Drinking water can also contribute meaningfully, depending on regional geology [8,9].

Interest in supplementation has grown alongside renewed scientific attention. Lithium orotate is widely available as an over-the-counter supplement, typically providing between 1 and 20 mg of elemental lithium per dose [15]. These amounts remain far below psychiatric dosing and are generally considered low risk for healthy individuals. However, it is important to emphasize that the optimal dose for cognitive protection has not been established, and existing human data remain limited in both size and duration.

At present, supplementation decisions should be approached cautiously and individualized. Low-dose lithium may prove beneficial as part of a comprehensive brain health strategy, but it should not be viewed as a standalone intervention or substitute for established lifestyle and medical approaches. Ongoing clinical trials and longitudinal studies will be essential for defining appropriate dosing, safety thresholds, and long-term outcomes, particularly in older adults and those with existing kidney or thyroid conditions.

A summary of common dietary lithium sources and their estimated contributions to daily intake is provided in Table 1.

Based on available dietary surveys and environmental measurements, typical daily lithium intake from food and water is estimated to range from ~0.5 to 3 mg/day, with individuals in low-lithium regions often falling at the lower end and those in high-lithium water regions occasionally reaching 5 mg/day or more [2].

Against this background, low-dose supplementation in the range of 5–10 mg/day represents a modest elevation above typical intake, intended to approximate the upper end of natural exposure rather than pharmacologic dosing. While this range may help compensate for low environmental lithium availability, current evidence supports viewing it as a potential adjunct to brain health and longevity, pending additional human trials data on optimal dose and long-term safety.

Synergistic Life Factors

Lithium’s potential benefits do not operate in isolation. Like many micronutrients involved in brain health, its effects are likely amplified by broader lifestyle context, interacting with diet, sleep, and stress regulation to support long-term cognitive resilience.

Dietary patterns rich in whole foods may be particularly relevant. A Mediterranean-style diet high in whole grains, vegetables, legumes, and healthy fats not only supports metabolic and vascular health, but also tends to provide higher natural lithium exposure, alongside antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds known to protect the aging brain.

Sleep is another critical habit. Lithium has long been recognized as a regulator of circadian rhythms, helping stabilize the sleep–wake cycle and support deeper, more restorative sleep. Given the strong links between sleep disruption, amyloid accumulation, and cognitive decline, this effect may represent an underappreciated pathway through which lithium contributes to brain health.

Finally, lithium appears to influence the brain’s response to chronic stress. By moderating excessive cortisol signaling, lithium may help protect neurons from the cumulative damage associated with prolonged stress exposure, a factor increasingly recognized as a contributor to cognitive aging.

Taken together, these interactions suggest that lithium’s role may be best understood as supportive rather than singular, functioning most effectively when embedded within a broader framework of healthy living.

The Rise of ⁷Li-MRI

To address this gap, researchers are developing Lithium-7 Magnetic Resonance Imaging (⁷Li-MRI), an emerging imaging technique capable of visualizing lithium distribution directly within living brain tissue using ultra-high-field (7-Tesla) MRI scanners [23]. This technology has the potential to transform both research and clinical application by allowing investigators to:

- Identify early vulnerability, detecting lithium depletion in key regions such as the prefrontal cortex, before overt cognitive symptoms emerge

- Monitor treatment response, determining whether lithium is reaching bioavailable neural tissue or being sequestered by amyloid pathology

- Personalize dosing, tailoring intake based on an individual’s unique brain distribution rather than peripheral blood levels

Although still largely confined to research settings, ⁷Li-MRI represents a critical step toward precision approaches in neurodegenerative prevention.

Clinical Trials and Translational Horizons

Several new lithium-based interventions are now entering formal evaluation. In 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved human trials of LiProSal, a novel lithium compound combining lithium with salicylate and proline, designed to enhance brain penetration while minimizing systemic side effects [24]. In parallel, Dr. Yankner’s group has announced plans for a clinical trial focused specifically on lithium orotate, aimed at defining safe and biologically effective dose ranges in humans.

These efforts mark an important transition from observational and mechanistic insight to rigorous clinical testing, an essential step for determining whether lithium’s promise can be realized safely at scale.

Interpreting Lithium Biomarkers: What Blood Tests Can and Cannot Tell Us

As interest in low-dose lithium grows, an important practical question arises - how can lithium status be measured safely and meaningfully in humans? At present, the most accessible tools are standard blood lithium assays offered by major clinical laboratories. These tests were developed for psychiatric monitoring, and understanding their limitations is essential when applying them to low-dose or nutritional contexts.

What Standard Lithium Tests Measure

Clinical lithium tests measure serum lithium concentration, reported in millimoles per liter (mmol/L). In psychiatric practice, these assays are used to ensure patients remain within a narrow therapeutic window, typically 0.5–1.2 mmol/L, where mood stabilization occurs without overt toxicity [15].

These tests are highly accurate and sensitive within that range. However, they were not designed to detect or interpret lithium levels near physiological or environmental exposure.

- Typical psychiatric treatment: 600–1200 mg lithium carbonate/day

- Corresponding serum levels: 0.5–1.2 mmol/L

- Environmental or microdose exposure: orders of magnitude lower

Can Low-Dose Lithium Be Detected in Blood?

Short Answer: Sometimes, but often, not reliably.

For individuals supplementing with 5–10 mg/day of elemental lithium (for example, via lithium orotate), serum lithium levels will typically fall:

- below 0.2 mmol/L, and often

- below the lower limit of quantification for many clinical assays

Even when detectable, values may fluctuate near zero depending on the timing of the blood draw, hydration status, renal clearance, and individual variation in absorption.

As a result, a “non-detectable” or very low lithium result does not imply absence of brain lithium, nor does it indicate supplementation failure. It simply reflects that common serum measurements are poorly suited for tracking trace-level exposure.

Blood Lithium Is an Imperfect Proxy for Brain Lithium

This limitation reflects a deeper biological issue emphasized throughout the article: blood lithium does not reliably reflect brain lithium availability.

- Lithium is actively transported into neural tissue

- Brain uptake depends on salt form, transport dynamics, and pathology

- Amyloid plaques can sequester lithium locally, further decoupling blood and brain levels

This is precisely why emerging tools such as ⁷Li-MRI are so promising; they aim to measure lithium where it matters, rather than relying on peripheral proxies.

Practical Guidance for Clinical Use

Until brain-specific imaging becomes widely available, blood lithium testing can still play a supportive but limited role:

Appropriate uses

- Establishing a baseline before supplementation

- Monitoring safety in individuals with kidney or thyroid concerns

- Confirming avoidance of psychiatric-range exposure

Inappropriate expectations

- Using serum lithium to “optimize” low-dose supplementation

- Assuming undetectable levels implies inefficacy

- Attempting to target psychiatric reference ranges for longevity purposes

For most individuals using lithium at nutritional or microdose levels, the goal is physiological sufficiency, not serum elevation.

A Shift in Perspective

This gap between measurable blood levels and biologically relevant brain effects highlights a broader theme of lithium research. Lithium may function less like a conventional drug, where dose and serum concentration track tightly, and more like a micronutrient, where tissue distribution, chronic exposure, and local availability matter more than circulating levels.

In this context, current blood assays are best viewed as safety instruments, not performance metrics. Their presence is valuable, but their interpretation must be aligned with lithium’s evolving role in brain health and aging.

Conclusion

The scientific narrative surrounding lithium is undergoing a quiet but meaningful transformation. Once viewed exclusively as a heavy-duty psychiatric drug, lithium is increasingly recognized as a biologically relevant micronutrient for the aging brain and healthspan extension. The convergence of epidemiological observations, molecular mechanisms, imaging advances, and early clinical signals supports a coherent hypothesis: that age-related changes in brain chemistry, particularly lithium depletion driven by amyloid pathology, may contribute to cognitive vulnerability and neurodegeneration.

While large, long-term human trials are still needed, the emerging data suggest that maintaining adequate lithium availability may represent a low-cost, biologically grounded approach to supporting cognitive healthspan. The lithium present throughout our environment in water, soil, and food underscores a broader lesson of aging biology: sometimes resilience depends not on introducing something new, but on preserving what the brain has quietly relied upon all along.

- Zarse, K., Terao, T., Tian, J., Iwata, N., Ishii, N., & Ristow, M. (2011). Low-dose lithium uptake promotes longevity in humans and metazoans. European journal of nutrition, 50(5), 387–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-011-0171-x

- Szklarska D, Rzymski P. Is Lithium a Micronutrient? From Biological Activity and Epidemiological Observation to Food Fortification. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2019 May;189(1):18-27. doi: 10.1007/s12011-018-1455-2. Epub 2018 Jul 31. PMID: 30066063; PMCID: PMC6443601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-018-1455-2

- Aron, L., Ngian, Z.K., Qiu, C. et al. Lithium deficiency and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 645, 712–721 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09335-x

- Shorter E. (2009). The history of lithium therapy. Bipolar disorders, 11 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00706.x

- Bauer, M., & Gitlin, M. (2016). Lithium and its history. In The essential guide to lithium treatment (pp. 25-31). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Strobusch, A. D., & Jefferson, J. W. (1980). The checkered history of lithium in medicine. Pharmacy in History, 22(2), 72-76.

- Cade JF. Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement. 1949. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(4):518-20. PMID: 10885180; PMCID: PMC2560740.

- Ohgami, H., Terao, T., Shiotsuki, I., Ishii, N., & Iwata, N. (2009). Lithium levels in drinking water and risk of suicide. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science, 194(5), 464–446. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055798

- Blüml, V., Regier, M. D., Hlavin, G., Rockett, I. R., König, F., Vyssoki, B., Bschor, T., & Kapusta, N. D. (2013). Lithium in the public water supply and suicide mortality in Texas. Journal of psychiatric research, 47(3), 407–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.12.002

- Zarse, K., Terao, T., Tian, J., Iwata, N., Ishii, N., & Ristow, M. (2011). Low-dose lithium uptake promotes longevity in humans and metazoans. European journal of nutrition, 50(5), 387–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-011-0171-x

- Bycroft, C., Freeman, C., Petkova, D., Band, G., Elliott, L. T., Sharp, K., Motyer, A., Vukcevic, D., Delaneau, O., O'Connell, J., Cortes, A., Welsh, S., Young, A., Effingham, M., McVean, G., Leslie, S., Allen, N., Donnelly, P., & Marchini, J. (2018). The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature, 562(7726), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z

- Huang, X., Huang, L., Lu, J., Cheng, L., Wu, D., Li, L., Zhang, S., Lai, X., & Xu, L. (2025). The relationship between telomere length and aging-related diseases. Clinical and experimental medicine, 25(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-025-01608-z

- Martinsson, L., Wei, Y., Xu, D., Melas, P. A., Mathé, A. A., Schalling, M., Lavebratt, C., & Backlund, L. (2013). Long-term lithium treatment in bipolar disorder is associated with longer leukocyte telomeres. Translational psychiatry, 3(5), e261. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2013.37

- Mutz, J., Wong, W. L. E., Powell, T. R., Young, A. H., Dawe, G. S., & Lewis, C. M. (2024). The duration of lithium use and biological ageing: telomere length, frailty, metabolomic age and all-cause mortality. GeroScience, 46(6), 5981–5994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-024-01142-y

- Hamstra, S. I., Roy, B. D., Tiidus, P., MacNeil, A. J., Klentrou, P., MacPherson, R. E. K., & Fajardo, V. A. (2023). Beyond its Psychiatric Use: The Benefits of Low-dose Lithium Supplementation. Current neuropharmacology, 21(4), 891–910. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X20666220302151224

- Abdul, A. U. R. M., De Silva, B., & Gary, R. K. (2018). The GSK3 kinase inhibitor lithium produces unexpected hyperphosphorylation of β-catenin, a GSK3 substrate, in human glioblastoma cells. Biology open, 7(1), bio030874. https://doi.org/10.1242/bio.030874

- Motoi, Y., Shimada, K., Ishiguro, K., & Hattori, N. (2014). Lithium and autophagy. ACS chemical neuroscience, 5(6), 434–442. https://doi.org/10.1021/cn500056q

- Ayata, P., Crowley, J. M., Challman, M. F., Sahasrabuddhe, V., Gratuze, M., Werneburg, S., Ribeiro, D., Hays, E. C., Durán-Laforet, V., Faust, T. E., Hwang, P., Mendes Lopes, F., Nikopoulou, C., Buchholz, S., Murphy, R. E., Mei, T., Pimenova, A. A., Romero-Molina, C., Garretti, F., & Patel, T. A. (2025). Lymphoid gene expression supports neuroprotective microglia function. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09662-z

- Pacholko, A. G., & Bekar, L. K. (2021). Lithium orotate: A superior option for lithium therapy?. Brain and behavior, 11(8), e2262. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2262

- Pacholko, A. G., & Bekar, L. K. (2023). Different pharmacokinetics of lithium orotate inform why it is more potent, effective, and less toxic than lithium carbonate in a mouse model of mania. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 164, 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.06.012

- Forlenza, O. V., Diniz, B. S., Radanovic, M., Santos, F. S., Talib, L. L., & Gattaz, W. F. (2011). Disease-modifying properties of long-term lithium treatment for amnestic mild cognitive impairment: randomised controlled trial. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science, 198(5), 351–356. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080044

- Nunes, M. A., Viel, T. A., & Buck, H. S. (2013). Microdose lithium treatment stabilized cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Current Alzheimer research, 10(1), 104–107. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205011310010014

- Stout, J., Hozer, F., Coste, A., Mauconduit, F., Djebrani-Oussedik, N., Sarrazin, S., Poupon, J., Meyrel, M., Romanzetti, S., Etain, B., Rabrait-Lerman, C., Houenou, J., Bellivier, F., Duchesnay, E., & Boumezbeur, F. (2020). Accumulation of Lithium in the Hippocampus of Patients With Bipolar Disorder: A Lithium-7 Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study at 7 Tesla. Biological psychiatry, 88(5), 426–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.02.1181

- Shi, Y., & Bryce, D. L. (2023). Ionic salt cocrystals studied via multinuclear solid-state magnetic resonance: a case study of lithium 4-methoxybenzoate: L-proline polymorphs. Canadian Journal of Chemistry, 102(3), 144-151.

Related studies